The Incomplete Wolverine – 1985

Part 1: Origin to Origin II | Part 2: 1907 to 1914

Part 3: 1914 to 1939 | Part 4: World War II

Part 5: The postwar era | Part 6: Team X

Part 7: Post Team X | Part 8: Weapon X

Part 9: Department H | Part 10: The Silver Age

1974-1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979

1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984

When we left off, Wolverine had disappeared from the pages of Uncanny X-Men for a few months to be in another miniseries. And here it is…

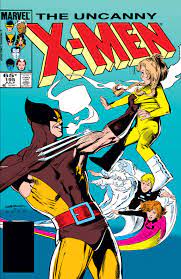

KITTY PRYDE & WOLVERINE #1-6

KITTY PRYDE & WOLVERINE #1-6

6-issue miniseries

by Chris Claremont, Al Milgrom & Glynis Oliver

November 1984 to April 1985

There’s a lot of plot here, so deep breath…

The Pryde family’s bank is in trouble because it’s just too generous in lending to local businesses. Kitty’s father Carmen sells out to new Japanese owner Heiji Shigematsu, actually a Yakuza obayun who intends to use the business as a money-laundering front. Kitty tails her father to Japan to learn all this, and gets captured by Shigematsu’s supposed “intermediary”, Ogun. Ogun brainwashes her and trains her as a ninja. But before she was captured, Kitty phoned Logan, and he duly shows up in Japan looking for her. Logan and Yukio fight a masked ninja who, you guessed it, turns out to be Kitty. Yukio drugs Kitty and the heroes regroup at a Clan Yashida stronghold, where Kitty seems to return to normal.

Wolverine explains that Ogun was his sensei, that he may or may not be a legendary samurai, and that he has imprinted his psyche onto hers, either through magic or psi-powers. Eventually this Ogun personality will overwhelm her entirely. The suggestion is that Ogun is basically a psychic parasite / ghost that moves from host to host. Conveniently for the plot, Logan believes that Kitty can only defeat Ogun’s influence by beating it herself. Logan mentors and trains her, and puts her through the same drills as Ogun, but gives her more choice, so that she has to make the decision to press on.

Kitty decides she’s ready to confront Ogun, and faces him alone as Shadowcat. She stops Ogun from killing Mariko. But with Ogun’s influence receding, Shadowcat’s ninja skills fade too. Wolverine shows up just in time to save her life, but he can’t beat Ogun in a straight fight either. He nearly surrenders in order to save her, but she encourages him to fight on. Finally, Wolverine defeats Ogun by going into a berserker rage. He tests Shadowcat by giving her the chance to kill Ogun, but she pulls back at the last minute. When Ogun tries one more time to kill her, Wolverine kills him. Wolverine wonders whether Ogun represented his true self, but Shadowcat tells him that he’s a man and a hero. Wolverine then destroys Ogun’s demon mask. (The mask will eventually resurface during the Larry Hama run, with the explanation that it’s a magic artefact that can’t be permanently destroyed through purely physical means.)

In the epilogue, Carmen goes to the authorities with what he knows about Shigematsu, ending his banking career. Mariko shows up to remind us that she can’t marry Logan until she’s proven herself worthy of him.

In the epilogue, Carmen goes to the authorities with what he knows about Shigematsu, ending his banking career. Mariko shows up to remind us that she can’t marry Logan until she’s proven herself worthy of him.

If this sounds more like a Kitty Pryde story, well, it is. It’s the coming of age turning point where she stops being written as the X-Men’s child member and becomes Shadowcat. But it’s also the story where Wolverine most obviously plays the mentor role to Kitty, and where he starts to take an explicit sensei role, in repeating Ogun’s training function. He’s kind of had this role in the past, chipping in with oddball training ideas and provocations, but this series sees him developing into a more conventional leader and teacher figure. In that role, he dresses in traditional Japanese style. In some ways, this shift of role makes Kitty Pryde & Wolverine as significant a turning point for him as the Wolverine miniseries; it completes his transition from being a violent brat to the voice of older wisdom.

His opening monologue in issue #3 flags up the oddity in his love of Japan: in America, Wolverine hates cities, and prefers the freedom of the mountains, yet he feels at home in what he describes as “probably the most structured society on earth”. The idea may be that he’s drawn to a society that seems to have sublimated its animal impulses. Intriguingly, the same issue has Logan tell Yukio that he can’t really explain what attracts him to Mariko either. (Mariko, by the way, is less of a stereotype than before; she’s started wearing business clothes, though she still treats it as part of the unwelcome chore of running the Clan.)

Kitty Pryde & Wolverine tends to be overshadowed by the Wolverine miniseries in memory, and there are good reasons for that – Wolverine had art by Frank Miller, for a start. But it’s a companion piece, and not just for the Japanese setting. Wolverine wins here by succumbing to his berserker impulses. Or rather, he moves beyond denying and suppressing his animal side, and starts harnessing it and being the best of both worlds. It’s a story that deserves more attention, at least in terms of its wider significance.

Rather embarrassingly, Amiko simply disappears after this point, not to resurface until the 90s. If Wolverine makes any further attempts to maintain a fatherly relationship with her, we don’t see it, and 90s stories show Amiko idolising him as a distant and mythical figure. A flashback in Wolverine: Black, White & Blood #3 shows Logan and Mariko packing her off to a boarding school in Yamaguchi, which presumably happens not too long after this miniseries.

WOLVERINE: EXIT WOUNDS

WOLVERINE: EXIT WOUNDS

“Aftermath”

by Chris Claremont, Salvador Larroca & Val Staples

June 2019

An old Japanese astronaut friend (sure, okay) asks Wolverine to help out his wife Hoshiko. Their family ramen shop, the Logan Noodle House, is under pressure from the criminal Goro, who wants Hoshiko’s family recipes. Kitty is surprised to see generations of family photos all featuring Logan, who seems to have married Hoshiko’s great-great-great-grandmother. The bad guys back off when they realise they’re messing with Mariko Yashida’s fiancé.

This is an anthology story, evidently intended to fit in this slot, given Kitty’s appearance. It’s something of an oddity, adding a chunk of unexplored detail to Logan’s back story, all in the midst of what seems to be a cooking manga pastiche.

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #192

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #192

“Fun ‘n’ Games”

by Chris Claremont, John Romita Jr, Dan Green & Glynis Wein

April 1985

These were the days when characters actually dropped out of the main title in order to appear in a miniseries, and so Wolverine doesn’t apear in Uncanny X-Men until April. And even then, he only appears in a subplot, where he and Kitty return to America. They’re met at the airport by Charles, Storm (who lost her powers while they were away), Illyana, Lockheed and Rachel Summers (who joined while they were in Japan). The group return to the Mansion just in time to miss a fight with Magus; Wolverine won’t meet Magus himself for a while.

There’s a lengthy gap between the main story and the epilogue (“some months later”), which doesn’t really concern us, because Wolverine isn’t in the epilogue. Strictly speaking, though, the following stories take place during that gap.

ALPHA FLIGHT vol 1 #16-17

ALPHA FLIGHT vol 1 #16-17

“…and Forsaking All Others” / “Dreams Die Hard…”

by John Byrne, Bob Wiacek & Andy Yanchus

November & December 1984

Logan drops by to offer his consolations following the recent death of James Hudson (which he learned about in Kitty Pryde & Wolverine #4). This is the story which includes an extended reprint from X-Men #109, re-dialogued to tell the story from James’s point of view. Puck also drops by, and he and Logan encourage Heather to take over as leader of Alpha Flight.

This story really hammers home that Logan and Puck are meeting for the first time, something which has been contradicted many, many times since.

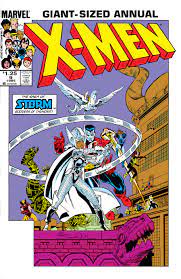

X-MEN ANNUAL vol 1 #8

X-MEN ANNUAL vol 1 #8

“The Adventures of Lockheed the Space Dragon and his Pet Girl Kitty”

by Chris Claremont, Steve Leialoha & Glynis Wein

1984

The X-Men and the New Mutants tell stories around a campfire. Illyana tells a pulp sci-fi story about Lockheed and Shadowcat, which is meant to encourage her to reconcile with Colossus and Storm. We also get a bit of Logan’s story. It’s about a samurai, and he delivers it in full-on storyteller mode, with dramatic gestures and language like “All was dark and supernally still as she mounted the hillside.” He’s camping it up outrageously, and it’s an interesting register for him. The story itself is intended to allude to Kitty’s recent experiences in Kitty Pryde & Wolverine, though it’s fairly oblique in doing so. (This is also the first time that Wolverine appears on panel with Warlock.)

ROM #65-66

“Doomsday!” / “The Day After!”

by Bill Mantlo, Steve Ditko, P Craig Russell, Steve Leialoha & Petra Scotese

April and May 1985

The X-Men are among a veritable horde of superheroes who show up to fight the Dire Wraiths as Rom nears its climax. Most of them Logan has encountered before, but he does meet Gremlin of the Soviet Super-Soldiers and Beta Ray Bill.

DAZZLER #38

DAZZLER #38

“Challenge”

by Archie Goodwin, Paul Chadwick, Jackson Guice & Petra Scotese

July 1985

Dazzler asks the X-Men for combat training. Most of the team are impressed, and invite her to join. But Wolverine thinks she’s only playing at being a superhero while her singing career is in a downturn. He also disapproves of her going public with her mutant powers, which he thinks was a career move that risked provoking an anti-mutant backlash. (1985 was a different time.)

To prove a point, she challenges Wolverine to ambush her whenever he wants. Once she’s back working as a lounge singer in San Diego, Wolverine and Colossus duly take up the challenge, and get beaten up, because it’s her book. Wolverine still won’t concede, but Dazzler feels she’s proved her point. This is macho nitwit Wolverine, and thus a few years behind his depiction in Uncanny X-Men.

WOLVERINE / NICK FURY: THE SCORPIO CONNECTION

WOLVERINE / NICK FURY: THE SCORPIO CONNECTION

by Archie Goodwin, Howard Chaykin, Richard Ory & Barb Rausch

1989

When Wolverine learns that old friend David Nanjiwarra has died in battle with Scorpio, he insists on joining Nick Fury’s investigation into Scorpio and his terrorist network Swift Sword. Scorpio is actually Nick’s previously unknown son Mikel Fury, brainwashed by his mother Amber D’Alexis. Wolverine kills Amber and Mikel surrenders for deprogramming. Despite the co-billing, this is Wolverine lending some star power to a Nick Fury story. Goodwin writes a decent Wolverine by this point, but the story really doesn’t need him.

This story has continuity problems. The basic problem is that it can’t happen when it was published, because the X-Men were feigning death in Australia in 1989 (and S.H.I.E.L.D. had been disbanded the previous year). Unfortunately, the X-Men make a cameo with a 1989-era roster, which doesn’t work at any point before Australia (there’s no earlier point where Colossus and Dazzler are both on the team). The official explanation is that Dazzler must have just been helping out for some reason, so it makes sense to stick this near Dazzler #38 – perhaps during her training visit.

X-MEN & ALPHA FLIGHT vol 1 #1-2

X-MEN & ALPHA FLIGHT vol 1 #1-2

2-issue miniseries

by Chris Claremont, Paul Smith, Bob Wiacek & Glynis Oliver

November and December 1985

When Scott and Madelyne’s plane crashes in a magical storm in Canada, the X-Men and Alpha Flight team up to investigate. They discover Scott, Madelyne and their passengers in a utopian magical city, all with super powers given by a magic “firefountain”. Madelyne has become the healer Anodyne, and she “heals” Wolverine by removing his berserker madness – which he’s very happy about, cheerfully announcing that he’s now “sane” and “human”. Kitty immediately points out that this ignores the moral of Kitty Pryde & Wolverine, but Wolverine is offended by the suggestion that he “can’t hack it as a man, only as a psycho.”

The firefountain will give everyone in the world powers, but it will eradicate magic. Everyone argues about whether that’s a price worth paying for global peace, and Wolverine is predictably on the “no” side. But when it turns out that the fountain also destroys the creativity of the people it empowers, everyone agrees it’s a bad thing. Loki, who created the fountain, throws a tantrum at this rejection – he was trying to do a good deed in order to impress the higher powers, Those Who Sit Above In Shadow. After the heroes beat Loki’s Frost Giant, Those Who Etc show up to tell Loki that by trying to force his gift on the humans, he missed the point. Loki promises revenge, and everyone else goes back too normal.

Wolverine meets new Alpha Flight member Talisman (Elizabeth Twoyoungmen) here. Madelyne reveals that she’s pregnant; the unborn child will be Nathan Summers, later Cable. And there’s a brief scene where Logan declines Heather’s veiled invitation to return to Alpha Flight, explaining that in his eyes, the X-Men are his family. He stresses that while he also regards Heather as his family, the rest of Alpha Flight are just friends.

(The reason for placing this so far out of sequence is that Professor X is using his powers freely; he gets beaten up at the end of Uncanny #192 and his injuries inhibit his telepathy for months afterwrads.)

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #193

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #193

“Warhunt 2”

by Chris Claremont, John Romita Jr, Dan Green & Glynis Wein

May 1985

The original Thunderbird’s younger brother James Proudstar declares himself the new Thunderbird, kidnaps Sean Cassidy, and challenges the X-Men to face him at NORAD headquarters. James has vowed to kill the X-Men to avenge the death of his brother, and his plan is to force them into a confrontation with the US military. But when Thunderbird actually encounters the X-Men, he can’t bring himself to kill them after all. On top of that, his Hellions teammates Empath (Manuel de la Rocha) and Roulette (Jenny Stavros), and the mind-controlled Firestar (Angelica Jones) have been interfering in his plan. Professor X convinces Thunderbird that he isn’t letting down his family by abandoning the vendetta, and Thunderbird and Firestar depart on good terms with the X-Men.

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #194

“Juggernaut’s Back in Town!”

by Chris Claremont, John Romita Jr, Dan Green, Steve Leialoha & Glynis Wein

June 1985

When the news reports that the Juggernaut is back, the X-Men track him down, but he seems just to be going about his business. Nimrod attacks the Juggernaut, and the X-Men help to drive the robot away. In the middle of this story’s battle, Wolverine is snatched out of time by Isbisa (Simon Meke) to appear briefly in Sensational She-Hulk #29 (July 1991), where he materialises in mid-strike in order to distract the She-Hulk. He’s returned to his own time with no memory of the diversion.

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #195

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #195

“It was a Dark and Stormy Night…!”

by Chris Claremont, John Romita Jr, Dan Green & Glynis Wein

July 1985

The Morlocks abduct Power Pack – at this point going by the names Gee (Alex Power), Lightspeed (Julie Power), Mass Master (Jack Power) and Energizer (Katie Power) – and try to make them into replacement children for Annalee, thanks to Masque’s deforming powers and Beautiful Dreamer‘s mind-altering powers. Energizer escapes, and gets help from the X-Men. Her siblings want to stay with Annalee, and other Morlocks try to defend them, including Leech and Sunder. Finally, Callisto shows up and orders that everything be put right. Power Pack decide to befriend Annalee, and amazingly, everyone seems to agree that this is a good idea.

Wolverine is noticeably kind towards Katie, insisting that she call him Logan rather than using his codename. He also keeps teasing Shadowcat about her role as acting field leader on this mission, but he’s clearly quite proud of her.

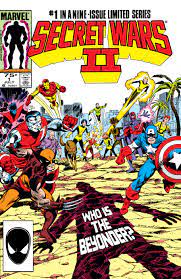

SECRET WARS II #1

SECRET WARS II #1

“Earthfall!”

by Jim Shooter, Al Milgrom, Steve Leialoha & Christie Scheele

July 1985

The Beyonder shows up on Earth in human form, looking for “experience”. Professor X senses his arrival, but he’s over on Muir Isle recuperating, so he asks Magneto to step in and lead – which the X-Men very sceptically agree to. The X-Men, Magneto, Dazzler, Cannonball, Magik and (for some reason) Lila Cheney pursue the Beyonder to Los Angeles. They wind up fighting Thundersword (Stuart Cadwall), an embittered screenwriter to whom the Beyonder has casually given super powers, and who is taking out his frustrations at Hollywood. (Cadwall is a parody of Steve Gerber, as seen from the perspective of Jim Shooter.) When Wolverine mistakenly thinks the Beyonder has killed some of the group, he claws the Beyonder, to no effect. Lila very sensibly teleports everyone away so that they can come up with a better plan. The Beyonder wanders off, and Thundersword winds up getting beaten by Captain America and Iron Man.

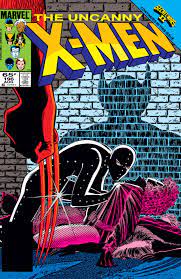

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #196

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #196

“What was That?!!”

by Chris Claremont, John Romita Jr, Dan Green & Glynis Oliver

August 1985

Professor X senses that one of the students in his lecture class is planning a murder, but his injuries prevent him picking up any more detail telepathically. So he asks the X-Men to investigate. They uncover a planned attack on the Professor himself, which is thwarted despite the disruption of the Beyonder showing up again (because this is a Secret Wars II crossover). It’s mainly a Rachel issue; this is the story where she reveals to the X-Men that she was a mutant-hunting Hound in her own timeline.

The Professor is still covering for his injuries, and gives a very unconvincing explanation of why he can’t simply read minds to find out the truth. Wolverine is obviously sceptical, but he’s willing to trust the Professor for now, mainly because he feels that the Professor is owed some loyalty. Magneto is still hanging around, and Wolverine argues that he should be given a chance to prove himself. Though Wolverine has his doubts, his instinct is that Magneto is genuine trying to switch sides.

I think this is also the first time that Wolverine points out that he can only smoke freely because of his healing factor.

Wolverine doesn’t appear in issue #197, in which Colossus and Shadowcat fight Arcade. Nor is he in issue #198, which is a Storm story.

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #199

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #199

“The Spiral Path”

by Chris Claremont, John Romita Jr, Dan Green & Glynis Oliver

November 1985

Moira MacTaggert tells Wolverine and Cyclops that Professor X is dying, and that he may be planning for Magneto to replace him as head of the school. Cyclops is appalled. Later, the debuting government-sponsored Freedom Force attempt to arrest Magneto while he’s attending a reception at the National Holocaust Center. The X-Men fight them, but ultimately Magneto surrenders, setting up his trial in the next issue. Freedom Force, of course, are the revamped Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, consisting of Mystique, Pyro, Avalanche, Destiny, the Blob and Spiral (“Ricochet” Rita Wayword).

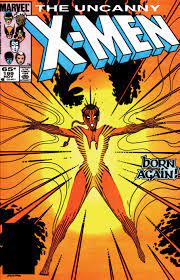

X-MEN ANNUAL vol 1 #9

“There’s No Place Like Home”

by Chris Claremont, Art Adams, Alan Gordon, Mike Mignola & Petra Scotese

1985

This is the second half of a crossover that began in New Mutants Special Edition #1. When Kitty receives a psychic message that Storm and the New Mutants are stranded in Asgard, Cyclops and the X-Men travel there to help. For this mission, Rachel makes her official debut in costume as the new Phoenix.

On arriving in Asgard, the X-Men save Wolfsbane’s boyfriend Prince Hrimhari from a group of trolls, whose souls are duly collected by Hela. The heroes split up, with Wolverine, Shadowcat and Phoenix finding half of the New Mutants. Everyone else is captured and brainwashed by Loki, who offers Storm a magic hammer that can restore her powers. Poisoned during an initial skirmish, Wolverine battles on to try and save Storm, convinced that it’s the last thing he’ll do before dying. When Storm assumes he’s a demon impostor and blasts him, Hela shows up to claim his soul. The X-Men, the New Mutants and the Valkyries hold Hela at bay, and she retreats in order to deal with more pressing business over in Thor #361-362 (where Hel is being invaded). Apparently that saves Wolverine’s life.

On arriving in Asgard, the X-Men save Wolfsbane’s boyfriend Prince Hrimhari from a group of trolls, whose souls are duly collected by Hela. The heroes split up, with Wolverine, Shadowcat and Phoenix finding half of the New Mutants. Everyone else is captured and brainwashed by Loki, who offers Storm a magic hammer that can restore her powers. Poisoned during an initial skirmish, Wolverine battles on to try and save Storm, convinced that it’s the last thing he’ll do before dying. When Storm assumes he’s a demon impostor and blasts him, Hela shows up to claim his soul. The X-Men, the New Mutants and the Valkyries hold Hela at bay, and she retreats in order to deal with more pressing business over in Thor #361-362 (where Hel is being invaded). Apparently that saves Wolverine’s life.

Loki eventually agrees to turn everyone back to normal and send them home, in exchange for not exposing what he was up to. As part of that, Storm and Wolfsbane give up their happiness in Asgard for the greater good. Sunspot quite liked the place too, which Wolverine dressed him down over, apparently on the basis that he was running away from the real world. Not sure that really makes sense in a world where Asgard exists, but there it is. This is mostly a New Mutants and Storm story.

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #200

UNCANNY X-MEN vol 1 #200

“The Trial of Magneto”

by Chris Claremont, John Romita Jr, Dan Green & Glynis Oliver

December 1985

Loki returns the X-Men and New Mutants to Paris, where Magneto’s trial for crimes against humanity is beginning. The prosecutor is Sir James Jaspers and the defence counsel is Gabrielle Haller, though Wolverine doesn’t really deal with either of them.

As the trial proceeds, the X-Men deal with a series of terrorist attacks made in their name, and demanding Magneto’s release. The real villains are Fenris – Andrea Strucker and Andreas Strucker – and the X-Men fight them at the court. Injured in battle, Professor X persuades Magneto not to be a martyr, and to quit the trial and take his place as leader of the X-Men. Magneto agrees, and Xavier is spirited away to the Shi’ar Empire for treatment.

Next time, in 1986, more of Secret Wars II, and the first of the annual X-crossovers.

Edited on 23 July 2021 to add the reference to Wolverine: Black, White & Blood #3.

[…] Next time, the Kitty Pryde & Wolverine miniseries (which starts in November 1984, but runs through to spring 1985). […]

Oh dear, Secret Wars II. One of the core (but not only) reasons for why 1985-1986 is such a bad period for Uncanny.

By this point Claremont had lost me completely. To this day I never read many of these stories, including the Kitty Pryde/Wolverine miniseries, which still strikes me as a fine example of bludgeon writing.

The whole premise is very inconsistent with the characters as previously depicted, but Claremont had a goal and he would not be turned away from it, character consistency be darned. Seeing it accepted so casually as a true and significant part of continuity destroyed quite a lot of my suspension of disbelief regarding the X-Men for good. I just kept waiting for reason to reassert itself, but it never did. And then the oddities just started to pile up without ever truly resolving. Charles now trusts Magneto for no good reason. Power Pack meets the X-Men and… I have no idea how they feel about it really. At this point I can only see the men behind the curtain and have stopped looking at the dummies being moved.

Not by coincidence, it is very much a time of proeminence for Wolverine. He keeps being treated as a character worth of some reverence just because. It really distracts me way out of the tales.

Things do start to get a little random for the X-Men at this point. Just looking at the list of villains from this year might give you tonal whiplash: Nimrod, Magus, Fenris, Loki, Beyonder, Arcade, Hellions, Freedom Force, mutant-hating humans, Morlocks, Ogun. Samurai, aliens, Nazis, Norse gods, and robots — oh my?

It’s surprising that Claremont was able to keep any long-form story-telling in place at all. The team is being batted about by an increasingly chaotic world, always reacting. I may be imagining this, but there might also be an uptick in the number of times characters are getting kidnapped and/or held against their will.

That said, it’s also the period that I associate with absolutely gorgeous X-Men special projects. Paul Smith on that X-Men/Alpha Flight mini, Art Adams on the X-Men/New Mutants Asgard story, the next couple years of annuals by Adams and Alan Davis. The main book (and New Mutants) might be losing focus at this time, but there are plenty of self-contained stories by top-notch artists to keep the mutant love alive.

I like the reformed Magneto, but a lot of readers who enjoy this change in character seem to forget there was no build-up towards this moment.

In #150, Magneto is definitely still a villain, but he becomes much more sympathetic as we actually learn about his past.

His next appearance is God Loves, Man Kills where he is depicted as an anti-hero at best.

Xavier and the X-Men still pointed out that they didn’t agree with Magneto’s methods or goals, even though he wasn’t the outright villain he had been in #150.

Then, it skips ahead to #200, where Magneto is facing a trial for his crimes.

At the end of this story, Xavier decides to make Magneto the new headmaster of his school.

There is a lot of story missing between God Loves, Man Kills that should have been filled in before we reach the point where Xavier and the X-Men (minus Scott) are able to trust Magneto.

Writers after Claremont make this story read even worse, as Magneto would end up a ranting lunatic wanting to kill everyone during the 1990s, which makes Xavier look like an idiot for completely trusting Magneto in #200.

I meant it skips ahead to #199-200…

What I liked about this period is how dark the stories were becoming, especially in the background.

Claremont was still writing superhero main plots, but there was an oppressiveness to a lot of the issues published in this period.

The anti-mutant hatred was building.

I’m not sure how much the reader was supposed to care about some of the villains that the X-Men were fighting in a lot of the Uncanny X-Men issues, as much as we were supposed to be concerned about the rising tension of prejudice against mutants.

If only there had been a pay-off to that direction, I think fans would enjoy this period of X-Men far more.

There really was a lot of creativity going in to the X-books of this period, as Thom discusses.

Also: Bill S doing artwork on New Mutants.

@ChrisV: between “God Loves, Man Kills” and #200 we had Secret Wars and Secret Wars II. Both, particularly the earlier one, put a lot of focus on Magneto and how the X-Men perceive him.

I don’t know that it _helps_. The X-Men and Charles Xavier all look very out of character in that regard to me. All of a sudden they simply decide that they may ally with Magneto even if the others don’t understand why they would, going so far as to establish a separate headquarters and to fight Wasp and later Spider-Man in order to keep their alliance secret.

They come out looking rather flakey to me, but apparently Claremont accepted that writing (by Jim Shooter IIRC) and ran with it. If you accept the characterization in Secret Wars I as convincing and legit (I do not) it probably should count as build-up for a reformed Magneto.

Even if it leaves me scratching my head and wondering what I may have missed.

I’m not entirely sure where this lands, and I’m too lazy to look it up at the moment, but doesn’t Magneto have a relationship with Lee Forrester somewhere between UXM #150 and #200?

I don’t recall that being a huge storyline, but it certainly nudges Magneto toward hating humans less, seeing that Lee is human. Maybe some of it happened in New Mutants — those books crossed over a lot at the time.

Poor James Proudstar. In the 80s he was a heroic character in a villain team. In the 00s he was a villain character in a hero team. Where did he go from “I just can’t kill my worst enemy” to “giant knives into everyone!”.

Thom H – on the Lee/Magneto relationship –

His satellite gets totaled by Warlock’s arrival in NM #21 and he’s found in the ocean by Lee in UXM #188. Then they go back to his island in NM #23, where they spend the next several months in New Mutants getting to know each other better (ahem) until Xavier asks him to help with the Beyonder in NM #29.

There are a couple of scattered narrative boxes—some of which come after Magneto has already become headmaster—where he credits his relationship with Lee for some of his changed attitude.

The steps on the way to Magneto’s reformation are: remorse at nearly killing Kitty in #150, revelation of his past friendship with Xavier in #16whatever, the relationship with Lee, and the 199-200, with lesser contributions from Secret Wars, Secret Wars II, and maybe GMLK (which was of dubious canonicity for a while). We also get a couple of classic X-Men stories that will explain his madness as being related to his powers affecting his mind (plus lots of personal trauma).

This could have amounted to a lot of development, but it’s all done at high-speed and mostly in subplots. Claremont had a weakness for speedy evil-good conversions: notice how Mystique goes straight from terrorist assassin and Pentagon spy to bring trusted leader of the government’s super-team. Magneto actually gets more setup for the turn than Mystique does.

Yeah, but Mystique is doing it for her own benefit.

Basically, Mystique and the Brotherhood saw the writing on the wall after the passing of the Mutant Registration Act and decided to sell out to The Man.

It’s not that I have an issue with Magneto’s changing. I think that was set up well enough.

If Xavier decided to give Magneto a chance, that would be perfectly fine.

It’s the fact that he suddenly puts Magneto in charge of the school and raising the New Mutants, with very little reason to trust Magneto.

If there had been a scene where Xavier and Magneto sat down and had a heart-to-heart meeting where Magneto admits that he has changed his mind about Xavier’s dream, I’d be more likely to see Xavier’s decision as rational.

Uncanny #195 was one of the first comic books I ever read. A friend had that issue and some Captain America issues from the same time featuring D-Man, Nomad and Diamondback. I read them over and over again. He also had a couple of OHOTMU and DC’s Who’s Who, which we studied like we were preparing for the bar exam.

Since this was my intro to the X-Men and Wolverine, his role as a mentor always felt natural to me. Especially since I didn’t start buying and collecting until a few years later. For several years this was not only the only depiction of Wolverine I knew, but it was practically the only Marvel comic book I had read.

I also had an outsized idea of the importance of D-Man.

I’ve got some of the issues from this period in X-Men Epic volume 12. That starts with Uncanny 198, but doesn’t have Kitty Pryde & Wolverine in it. I hope it’s in volume 11 when that comes out. Should be, as 12 has not only the Alpha Flight mini but also the Nightcrawler mini from that time.

Right there with Thom H. on those side projects. The two Loki tales are personal favorites – just fun, well-drawn adventures featuring characters we love.

“The steps on the way to Magneto’s reformation are: remorse at nearly killing Kitty in #150, revelation of his past friendship with Xavier in #16whatever, the relationship with Lee, and the 199-200, with lesser contributions from Secret Wars, Secret Wars II, and maybe GMLK (which was of dubious canonicity for a while). We also get a couple of classic X-Men stories that will explain his madness as being related to his powers affecting his mind (plus lots of personal trauma).”

Uncanny 196 is a pretty big step as well. The one where he acts as something of a mentor to Rachel in the ending scene.

What Nu-D doesn’t realize is that because of an as-yet-unpublished time travel story slotted for MARVEL FANFARE #61 D-Man is ACTUALLY the secret inspiration for one of the versions of THE DEFENDERS

Jason-Yes, #196 is a very important issue.

It’s been quite a few years since I reread the Claremont issues again, and I have forgotten many details.

I thought that scene happened after Xavier made Magneto headmaster. That’s a very important scene, showing how Magneto has changed. He shows mercy on the humans who wanted to kill anyone for being a mutant.

In my mind, Magneto didn’t appear in any of Claremont’s comics between God Loves, Man Kills and #199, but that’s incorrect.

I guess Xavier choosing Magneto to run the school was built up in the prior comics.

Chris V, I think you make a good point, though. When it happens in issue 200, it’s still a bit of a shock. When you work backwards after it happens, you can see that Claremont was laying the groundwork for it, but I agree that it’s rather surprising and abrupt in the moment.

Granted, that may have been part of the point. Xavier didn’t know that he was going to be teleported up by the Starjammer at the end of issue 200, and that he’d have to spring the headmaster gig on Magneto right in that moment. Presumably he thought he’d have a bit more time to ease Magneto into the idea.

And the X-Men and New Mutants’ reaction afterward has a definite “What was Xavier thinking?!?” vibe that also suggests the abruptness of the plot turn was a deliberate element to it all.

“I also had an outsized idea of the importance of D-Man.”

This is so great. 🙂

I’d like to think we all (comics fans) have characters like this in our personal mythologies based on when we first came into collecting certain series.

Claremont would quickly shift characters from “bad” to “good” and then have them doubt their worthiness to be included by the X-Men. Wolverine is probably the prototype here, but then Rogue and Magneto go through similar phases. “They don’t trust me, but why should they?” (or similar) was a frequent refrain for all of them.

Magneto got a little more build-up from “bad” to “good” than most, probably. Even so, I agree it was pretty abrupt. Not as abrupt as Rogue just showing up to the mansion and being declared a member of the team, but Magneto had more of a history to overcome.

There was even a watered down version of this trope for the New Mutants in which a character would join the team as a rebel or loner and then quickly lose their edge as their teammates accepted them. Mirage went from fiercely independent to team leader pretty quickly, with all the attendant uncertainty about accepting the role. 80’s Claremont liked to write about self-doubt, I guess.

Morrison kind of turned that idea on its head with Emma in New X-Men. She seemed quite sure of herself — and still a little bit bad — the entire time she was on the team.

I liked the idea of former-villains accepting Xavier’s dream in the end.

It’s supposed to be a very powerful message. It would only make sense that it would eventually begin to appeal to those who originally refused to accept it.

It gave a message of hope. That individuals can change.

It also plays in to part of Xavier’s dream: forgiveness and redemption.

Everyone deserves to be given a chance.

Claremont’s run, at heart, seemed to embrace the idea that almost any mutant was redeemable.

The same didn’t seem to apply with humans.

Perhaps part of that is reading too much in to the story, as Claremont didn’t want to continue to tell the same superhero plots, ad nauseam. Reforming villains was one way to move on from having to tell X-Men vs. Magneto battle no. 123.

Unfortunately, the message seemed to only be one-way.

We rarely saw humans changing their views in return.

There was more of the opposite, with all the doom and gloom about the “Days of Future Past” looming.

Morrison’s run would see the change from the other direction.

The insecure reformed villain has a long history in Marvel comics, from Wanda and Pietro, to Wonderman, to Rogue and Magneto, and so on. Claremont was not exactly treading new territory here.

Except that previous implementations of that plot (nearly all of them in the Avengers) were all about the remorse and repentance, with hardly any ambiguity or grey areas. The only exception that comes to mind is Swordsman.

While I do think that Claremont overextended himself, I acknowledge that his attempts were original when compared to previous villains-turned-heroes.

He was certainly much more ambiguous about it and I honestly don’t know that he even attempted it in some cases.

Wolverine, Magneto, and at times Storm are all very, very far from the typical “face turn” scenario. And there are even subtler situations, such as Colossus’ time with the MLF or the uneasy interactions with the Hellfire Club, the Morlocks, various Madrippor factions, Cable and X-Force.

If anything, Claremont can be argued to have given up on writing the X-Men as heroes and transitioning them into the prototype for the current setup as a national group with shady ethics.

Luis: And there are even subtler situations, such as Colossus’ time with the MLF…

Do you mean Colossus’ time with the Acolytes? Either way, that’s a post-Claremont thing, no? (Was the MLF even introduced until after Claremont left the books?)

“This is macho nitwit Wolverine, and thus a few years behind his depiction in Uncanny X-Men.”

He still is when modern writers need a guest jobber to prop up their main character.

“Oh dear, Secret Wars II. One of the core (but not only) reasons for why 1985-1986 is such a bad period for Uncanny.”

Just the opposite, actually, the Secret Wars II issues are really good ones.

“even though he wasn’t the outright villain he had been in #150.

Then, it skips ahead to #200, where Magneto is facing a trial for his crimes”

Issue #196 is part of that journey as much as the Secret Wars issues, even if people seem to ignore it.

Good to know Claremont was carrying on a fine Marvel tradition. I’ve never read early Avengers, so all I know of ’60s Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver is their doubt about being part of Magneto’s crew. I guess they were going to be insecure either way.

I do think the mutant angle puts a new light on the reformed villain trope. Rogue, Magneto, Emma, etc. all belong to the mutant “tribe” no matter their bad behavior. Humanity’s fear and hatred of mutants means they have more in common with the X-Men that they (or the X-Men) want to admit. Clever of Claremont to re-contextualize the trope for his own purposes.

The MLF was created while Claremont was still writing Uncanny X-Men. It was one of Rob Liefield’s earlier creations on New Mutants.

Colossus had nothing to do with the group though.

When you look at the fact that issue #196 was billed as a “Secret Wars II” tie-in issue, I would have to agree with the sentiment that the tie-in issues were very good.

I’d say it is in spite of being part of that mess though rather than anything to do with it.

I liked the description of the Beyonder as editor-in/chief Jim Shooter wandering in to the plot to try to tell the creators what to do with their story. Claremont is just going about his business, telling his X-amen story, and this 1980s mod guy shows up to try to intrude in Claremont’s on-going plot.

I love that auto-correct always wants to change “X-Men” to “X-amen”.

It’s been a long while since I’ve read those Silver Age Avengers issues, but we mustn’t forget the continuous insecurity by Quicksilver that he’ll be able to protect his sister. That’s what I most strongly remember about the early Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch characterization.

Beyond Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, the Avengers also encouraged the rehabilitations of Hawkeye, Black Widow, Wonder Man and Swordsman. Later there were also Deathcry and (a) Masque. Even the Vision started life as a weapon to destroy the Avengers.

Sorry, I confused the MLF with the Acolytes. Didn’t Colossus defect to Magneto’s side during Claremont’s very last story of his original run, in early issues of adjectiveless X-Men?

Secret Wars II is strange in so many ways. It looks hurried to me, not least because the art was so scratchy and several key scenes very generic, perhaps in order to be easily retouched with suitable dialogue.

Even so, I seem to be in the minority that liked it better than the previous event. Between the odd characterization and Mike Zeck’s art I did not enjoy the first Secret Wars much.

And frankly, there were lots of interesting (if wildly inconsistent) SW2 crossovers back in the day. The role of the Beyonder in the last few issues of New Defenders is particularly bitter, and he had interesting roles in the Fantastic Four issues as well.

No, Colossus defected to the Acolytes after Illyana died of the Legacy Virus.

It was one of the worst, most nonsensical X-stories.

I’m pretty sure it was Nicieza.

Claremont wanted Colossus to leave the X-Men behind and become an artist, but Harras overruled Claremont, and had Colossus appear out of nowhere half-way through the “Muir Isle Saga”.

That might have been what finally made Claremont decide to quit at the half-way point of his final Uncanny story-arc.

Claremont didn’t want to use Colossus as a X-Man, so he was completely absent from X-Men #1-3.

Claremont was right about Colossus too.

He was one of the few well-adjusted mutant characters, and he just wanted to find peace.

No other writers had any plans for him.

He went from a person who could leave the X-Men behind and become an artist, to a character that writers felt had to be made as depressing and gloomy as possible.

The only thing writers did with him in the 1990s was to strip him of everything that made him happy, until they finally decided to kill him.

Storm becoming a non-entity after Claremont is a massive crime, but I would say there is no bigger character assassination of a X-Men character after Claremont than Piotr.

Plus, Claremont had run out of stories to tell with Ororo before the end as well…it was all downhill after he randomly decided to turn her in to a child.

To tie into the other pod, songbird also will eventually be an Avenger and one of Hawkeyes motivations for leading the Thunderbolts (IIRC) is to pay forward what Cap did for him.

Claremont didn’t want to use Colossus as a X-Man, so he was completely absent from X-Men #1-3.

The first part may be true, but the second is not.

ASV – That’s spot on. He hasn’t got a major role but he’s certainly there and features in a particularly memorable moment during the Danger Room battle when Archangel drops him into the mansion like a wrecking ball.

The art in that issue is absolutely fantastic. I remember being 14 and picking it up for the first time and being blown away by Claremont and Lee’s work.

Secret Wars II has some stupidity in it, but I liked the general idea of the god-like being deciding to make himself mortal. And I have fond memories of lots of the tie-ins from all around the MU in the weekly UK title. The 2 SWs were my introduction to X-Men, and made me a Marvel fan.

I loved Secret Wars 1. The same friend who had Uncanny #195 and the D-Man issues of Cap, also had a bunch of Secret Wars figurines. We loved playing with them. For some reason, each one had a shield with a “hologram.”

But as a reader of Uncanny, SW2 was terrible to read in back-issues. The tie-ins were totally decontextualizad, and made no sense. I read them years after publication, and they were incomprehensible without knowing what was going on elsewhere in the line. Eventually I got my hands on the mini, but it was so bad I never finished reading it. From the perspective of the X-Men, the whole event is worth forgetting.

Chris V:

“That might have been what finally made Claremont decide to quit at the half-way point of his final Uncanny story-arc.”

Per Claremont, he left because Harras kept shooting his ideas down, and eventually decided to not let him plot the book anymore.

(Too bad he didn’t try toughing it out a few more months… He may have had a chance to regain control after the Image announcement.)

“Claremont didn’t want to use Colossus as a X-Man, so he was completely absent from X-Men #1-3.”

Colossus appeared in spots (the intro sequence, the X-Men vs. X-Men stuff in #3) – the reason why he didn’t appear more was because he was on the Gold team (who were to be the focus of Uncanny), not the Blue.

Claremont had planned on having Colossus play an important role in a Wolverine storyline that was shot down so I don’t think he was that upset about having him back on the team.

[…] of a very big number, double it, then recognize that this number will still pale into insignificance compared to the number of comics that Wolverine appeared in in the […]

@Walter Lawson

The speedy evil-good conversions have gone into warp speed today, with monsters like Apocalypse, Daken, and Gorgon getting a pass because they’re cool. Xorn and Esme Cuckoo killed upwards of a million people in Manhattan and have resurrected into good lives on Krakoa. Even Proteus, written by Claremont as absolute evil, is now a beloved hero there.

@Chris V

As I think you’ve said, Claremont seemed to be working towards a redemption arc for Nimrod. From the beginning, Sen. Kelly (an Edward Kennedy expy) was described as a good but misguided man who ultimately became pro-mutant and was assassinated by an anti-mutant terrorist. In X-Treme X-Men, he redeemed an anti-mutant suicide bomber and even Rev. Stryker.

@Luis Dantas

Even if the X-Men became outlaws, Claremont still wrote them as heroes.

I don’t know when Daken became the hill I’m willing to… maybe not die on, but be severely inconvenienced… but Daken had plenty of stories where he wasn’t a monster before the Krakoa era. The fact that Sina Grace used him as a stab-happy sociopath (which was his last pre-Krakoa appearance, I believe) was a throwback to Daken’s earlier portrayal. He was shown to be able to work with others and have normal relationships with people, he had a redemption arc (…of sorts) in the deeply weird Wolverines… He was basically at a point where he was a raging psycho towards Logan and pretty normal towards everyone else.

@neutrino

It got generally better since, but ever since Uncanny #170 or so – or even before, such as that issue where Carol met Rogue again while sabotaging the government’s databases – Claremont had clearly been writing the X-Men as sliding ever away from a fairly visible, clearly heroic and at times even government-associated group (mostly by way of Fred Duncan, but also colaborations with General Ross and others) into something better described as an independent militia that more often than not had fairly idealistic goals, but was also prone to rather alarming missteps and quite a lot of dangerous inner conflict.

It quite explicitly wasn’t consistently heroic, and I don’t expect that Claremont wanted us to perceive it as such.

That trend is perhaps representative or even an early occurrence of a more general cultural trend towards a less idealistic, more cynical morality, but I don’t think that we can very well argue that it did not happen.

I would love to elaborate on that trend, but probably not here. It is something of a controversial subject.

Dave-I know that Claremont decided to quit writing X-Men because Harras had been taking more control over the plotting of the comic.

Claremont wanted to be professional and finish the three-part “Muir Isle Saga” story before he left though.

Instead, he ended up quitting as writer half-way through the three-part story. I was hypothesizing that it was Harras forcing him to bring back Colossus that made him quit in such a way…not that it made him decide to quit the X-Men initially.

I had never heard that Claremont had plans to use Colossus during the “death of Wolverine” story though. That’s interesting.

Luis-I would say that Claremont was writing the X-Men more as outlaws or revolutionaries, rather than outright superheroes.

I would argue he was still writing them as heroes.

They continued to stand by their “X-Men don’t kill” morality.

During “Fall of the Mutants”, with the Adversary, the X-Men still risked their lives to save the world.

He wanted us to sympathize with the X-Men.

His writing on the X-Men was still a far cry from the anti-hero trend, like with Punisher or during the early-‘90s with characters like Venom.

The X-Men were operating under the shadow of the fact that in a future world the government was involved in a genocide campaign against mutants.

The world of the X-Men was a much darker reality than that for the Avengers or the FF. Those characters could be shiny bastions of pure superherodom, as they were accepted and celebrated by the public.

That works up to a point. It just happens that the X-Men went way beyond that point.

I am honestly not sure that we _were_ meant to sympathize with the X-Men after, say Uncanny #150, let alone after the uprising of the mutants in Secret Wars.

You may probably perceive that as a self-fulfilling prophecy if you want to.

Myself, I see that as a simple, deliberate decision by Claremont to have the X-Men drift from something roughly comparable to a FF that happens to recruit new members every now and then into a mutant IRA of sorts. The clearest sign of that shift may well be the period between God Loves, Man Kills and Uncanny #200 (or was it Avengers vs X-Men?), when Magneto presents mutantkind as a oppressed nationality of sorts and Gabrielle Haller eventually formalizes that claim in an attempt to defend him in court.

Leaving aside for a moment the merits (or lack thereof) of the claim itself, by that point the X-Men had at the very least accepted not to challenge it.

So no, they were no longer heroes except by circunstance at that point. They were a superpowered militia with moral compasses that were often erratic and _far_ more often than not mainly self-serving.

@Chris V

‘They continued to stand by their “X-Men don’t kill” morality.’

Well… it might be more fair to say they try to. Sometimes.

As Paul mentioned repeatedly, they balk at Logan killing people, but they don’t actually stop him. (Ororo comes closest when she asserts her leadership, telling him he’ll only use his claws when she tells him to, which he accepts).

Logan then undergoes a really weird… I’ll call it a phase, since it’s not actually a permanent change… where he’s willing to kill Rachel to prevent her from murdering Selene, which is… I’ve read it recently and I have no idea what Claremont was doing there.

But. Colossus kills Proteus and it’s a win for the team. They all, even kill-averse Cyclops, in the end are fine with wiping out the Brood. Later Colossus kills Riptide and the X-Men are more then fine with that. Storm literally orders Logan to bring her a prisoner, singular, and kill the rest of the Marauders if he has the chance.

Rogue has a weird line there where she’s against Colossus killing Riptide only because ‘it’s Logan’s or [her] job’ – I guess that’s meant to be the Danvers personality, since Rogue doesn’t kill… yet? (I honestly don’t know, I’ve yet to read the Australian era).

Anyway, at that point the X-Men are basically set to kill Marauders on sight. They won’t actually get the chance to do it, but that’s their intent.

The extreme of this willingness to kill comes probably when Psylocke suggests killing Havok when he discovers the X-Men and Storm doesn’t rule it out immediately.

And Havok will attempt to kill the Malice-possessed Polaris soon after.

So it’s more like ‘the X-Men don’t kill unless they do’ or a case of ‘do as the X-Men say, not as they do’.

Their stance on killing gets pretty nuanced during the Australia period. They have a debate about killing the Reavers right in the first issue of Australia, where Wolverine and Psylocke are pretty on board with killing the defeated Reavers, whereas Havok makes a joke about it and Colossus is opposed. Storm ultimately opts to send them into Siege Perilous.

But by the time we hit Inferno, Storm very deliberately kills N’astirh, and when Cyclops challenges her on making herself judge, jury and executioner, her response is “I lead the X-Men. It is my duty… and my right.” Storm’s established as being increasingly comfortable with using lethal force in fights, but Claremont’s drawing a line between her and Cyclops on this.

Meanwhile, Wolverine is Wolverine. Psylocke and Havok both consider using lethal force during the first Genosha arc. Inferno kicks off with the X-Men explicitly on a mission to kill the Marauders, which they do, and Psylocke is downright giddy when she tricks and kills Scrambler and Arclight. Havok spends much of Australia worrying about accidentally killing people with his plasma blasts, but there’s a moment at the end of Inferno where he straight-up kills Blockbuster, and when Dazzler asks about it, he just says “I’ve changed.” Dazzler, Longshot and Colossus remain opposed to killing throughout, and Rogue is surprisingly not really involved in the debate at all, but that’s still half the team now willing to kill in battle by the end. (And then the whole subject basically gets dropped post-Australia.)

Chris V

Gotcha. My interpretation of his comment was that the decision to not let him plot anymore was made while he was working on #279 so that’s when he decided to quit. What led me to that conclusion was that Muir Island wasn’t supposed to end the Shadow King story; just be the next act in it, so…

Luis

Making my way through the Claremonts now (just finished Fall of the Mutants). I’d say you’re still supposed to feel sympathy for them. They’re trying to do the right thing (while still protecting their own), but you have a mutant killing robot cheered as a local hero (Nimrod), the Government is passing legislation about them, Storm just had her powers taken from her by a Government agent, etc., and it starts to get to them.

One thing I think blurs the lines a bit is that Claremont seemed to start writing the villains more sympathetically than he had at first. They’re just trying to make their way in the world; they just don’t necessarily make the right choices. You have your occasional straight up bad guys like the Marauders or the Adversary. But others are just crooks or misguided, not monsters. As a result, attempting to defeat your enemies by convincing them to switch sides (see Rogue and Magneto) becomes a tactic.

Krzysiek

Just re-read #207 myself. Wolverine, and the X-Men in general, had a tendency to differentiate between killing someone in battle and breaking into their house for the sole purpose of killing them. If Selene had attacked Rachel and Rachel killed her, then Wolverine wouldn’t care so much. I also got a sense of residual concern after what she did in #203 and how she might be following her mother’s lead.

“Rogue has a weird line there where she’s against Colossus killing Riptide only because ‘it’s Logan’s or [her] job’”

I thought it was weird that it came from Rogue, but it’s not usual to want your idealistic friends to stay idealistic.

“The extreme of this willingness to kill comes probably when Psylocke suggests killing Havok when he discovers the X-Men and Storm doesn’t rule it out immediately.”

Now THAT one threw me. The only way I can get that one to make sense is to assume we’re getting the scene filtered through Havok’s perceptions and that a more “third person” telling of the scene would have come across differently.

Allan M

Not sure Inferno is the best example. The X-Men all got a little crazy during that one.