Daredevil Villains #47: Brother Zed

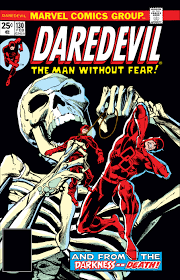

DAREDEVIL #130 (February 1976)

DAREDEVIL #130 (February 1976)

“Look Out, DD – Here Comes the Death-Man!”

Writer, editor: Marv Wolfman

Penciler: Bob Brown

Inker: Klaus Janson

Colourist: Michele Wolfman

Letterer: John Costanza

Once again, we’ve skipped some issues. Issues #126-127 are the debut of the Torpedo, a rookie rival superhero who does the obligatory misunderstanding-and-fight routine. He actually had some legs: he returns in issue #134 as a supporting character, then gets a try-out as a solo hero in Marvel Premiere , and finally winds up as a supporting character in Rom. But he’s not a villain, so he’s outside our remit. Issue #128 is another Death-Stalker story. And issue #129 brings back the Man-Bull.

In fact, focussing on the new villains will give us a rather unrepresentative view of Marv Wolfman’s run. He’s the first writer who seems to have looked at Daredevil’s pre-established rogue’s gallery and deemed them to be basically serviceable. There are only a handful of new villains in his run. And one of them is a very big name, but we’ll get to him.

It’s not that Wolfman didn’t create new characters for the book. He absolutely did, but they were mostly supporting characters. As well as the Torpedo, the issues we’ve skipped introduce Daredevil’s new love interest, Heather Glenn. We might not have much reason to talk about her here for a while, since her first major storyline involves the Purple Man, but she’s a major character who’ll stick around well into the 1980s. At this point, she’s a sort of prototype manic pixie dream girl.

Wolfman also brings in Blake Tower as the new DA, largely to take over Foggy’s plot advancement function once he left the job. And there’s a grumpy cop called Bert Rose who hates superheroes; he’s a recurring presence for a few years until he gets quietly dropped without ever having a storyline of his own.

Issue #130 also introduces the Storefront, Matt’s new operation giving free legal advice to the poor. Later issues will explain that Heather is an heiress and that daddy is paying for all this. We haven’t quite reached Daredevil as the protector of Hell’s Kitchen (the Storefront is on the lower east side, for one thing), but we’re much closer than before.

But we’re not here to talk about any of that. We’re here to talk about Brother Zed. And he hasn’t aged well.

Brother Zed is the houngan of a group of voodoo worshippers, all apparently Haitian immigrants. Zed appears to them as a burning skeleton. We first encounter him as he’s shaking down one of his worshippers for money, claiming that if she doesn’t pay up, the loa will take her son. She goes on the run and tries to get help, but her friends are all fellow worshippers who won’t break ranks with Zed. Eventually, Zed’s followers catch up with them and drag her off to Central Park, intending to sacrifice the boy, apparently so that Zed can teach everyone an important lesson about what happens if you don’t give him money.

Naturally, Daredevil happens to swing by, and he breaks up the human sacrifice. This being a 1976 voodoo story, Zed tries to kill Daredevil with a voodoo doll. But as soon as Daredevil gets close, he just kicks Zed in the face. The twist is that Zed is just a guy in a dodgy skeleton suit who has some low level hypnotic powers that make him look impressive to his followers. But as usual in this book, hypnosis doesn’t work on blind people, and so Daredevil isn’t even entirely sure why everyone else seems so impressed by this loser in a cheap Hallowe’en costume.

You will doubtless have noticed that this story features black people. Now, it’s 1976, and we’re not in the Silver Age any more. In some parts of the Marvel Universe, black people with actual dialogue are no longer a novelty. Luke Cage has been around since 1972; Storm debuted in 1975. But none of this had fed through to the pages of Daredevil, which was still overwhelmingly white at this point. The only significant non-white supporting character, Willie Lincoln, hadn’t appeared since issue #59.

Now, to be fair, crowds of bystanders were starting to get more diverse. And issue #127 had featured a fairly normal black family, living in low income housing in Westchester County. Their role was to have their house smashed up by the fight between Daredevil and the Torpedo, and then give both heroes a stern dressing down about the whole thing so that they can feel guilty about it. Technically, nothing about their role turns on them being black, but they’re clearly intended as a shorthand for the dignified urban poor.

And this is a story about voodoo.

To be fair, if the context included a wider range of black characters, this particular issue wouldn’t be so bad. In some ways, Zed’s worshippers do avoid cliche. The story pitches them as ordinary folk who are being taken advantage of. They aren’t straightforward zealots – Zed’s using illusion to exploit their religion. At its root, this is meant to be a story about a group of immigrants who are bound together by their shared religion, and the cynical priest who exploits their unity and culture by turning them into his cult.

There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with that. You could do it with a fringe Christian group and the plot would basically work. Maybe you could make an argument that voodoo just happens to be a more visual option. Viewed in this way, the biggest problem with the issue is the rather pat resolution after Zed’s defeat, where his followers take all of one page to realign their worldview after his illusions are exposed.

But the bottom line is still that black characters rarely get much to do much in mid-1970s Daredevil, this issue is a rare exception, and what do you know, they’re a gullible and easily manipulated bunch who are a danger to themselves and who spend their evenings decapitating chickens in Central Park. They get a lecture from Daredevil about responsibility. In the context of Wolfman’s run as a whole, this was probably intended as a more general “think for yourself” message – he’ll come back to that theme in a major Jester storyline about disinformation and deepfakes. But the way in which it’s played here doesn’t look good.

Brother Zed never returns, but he was clearly designed as a one-off villain. His routine is very specific to this story and this group of followers, so it doesn’t lend itself to repeat appearances. Still, it isn’t hard to imagine a version of this story where the voodoo was a bit less cliched, and the abuse of position angle came across more strongly. Zed himself isn’t a terrible villain; the problems stem more from the context in which he appears.

At a guess, this is meant to be a meta twist, since Wolfman was writing horror books for Marvel. Perhaps Brother Zed is meant to subvert reader expectations because he isn’t actually supernatural like the “voodoo” villains who appeared in Wolfman’s Tomb of Dracula and Werewolf by Night stories.

The shame of it is, it seems like there’d be room for some kind of fringe-Christian cult leader type in Daredevil’s rogues gallery. The legal questions around exploitation and the whole supposed brainwashing/deprogramming thing would work. And later writers would make a lot out of Matt’s own tortured Catholic faith.

The closest things we’ve ever gotten to that have been the Hand, usually portrayed as an unambiguously evil demon cult, and Mysterio’s use of religious motifs to mess wirh Matt in the “Guardian Devil” arc. Seems like a missed opportunity.

I mean, Brother Zed would never have been it, but…

Ah, 1976 Marv Wolfman writing. You will notice it.

You will find it corny, you will wonder how come this is the same guy writing Tomb of Dracula at the same time, you will notice that he already has a thing for new love interests and inclusivity, you will be amazed at how kooky early Heather Glenn is. But you will notice it.

In some ways Wolfman reminds me of Claremont. To reference a popular saying, both men had reaches that exceeded their grasps. They attempted to give characters more depth and relatability than it was usual for the times, and sometimes that worked, while sometimes if very much did not.

Many of the distinctive traits of the work that made Wolfman a big name (1980s “New Teen Titans”) are already starting to insinuate themselves here, four years prior. Themes of reputation and biased news, of sexuality and attraction and how they can be messy, of social issues and how it is dangerous to ignore them.

But at this point those marks don’t quite coalesce in the way they will in 1981. Daredevil’s version of Marv Wolfman more closely resembles the one we see in Nova, with a lot of retro trappings mixed with a very Spider-Man-like focus on everyday minor nuisances.

The best way to approach his work in this book may be as a training ground of sorts, a work lab where some of his ideas get room to breathe and develop into more mature forms.

I was almost eight years old at the time, but I don’t know that public perception in late 1976 was ready for mainstream American comics presenting dangerous fringe Christianity as a real thing that did exist.

Jonestown would be a significant wake-up call, but that is still a year or two in the future. It has been almost fifty years since and I don’t think the public is even now quite mature enough to deal with those themes, although I would love to be proven wrong. The best piece of counter-evidence that occurs to me would the 1988 miniseries “Batman: The Cult” by Jim Starlin.

Issue 128 is odd- it features a new character called Sky-Walker, who’s walking into outer space on steps made out of solid light. But he’s not really a villain- although at the end he does say that if he’s forced to return to Earth, he may be the death of Daredevil. And then the guy disappears- he only shows up again in a Quasar issue as one of the Stranger’s prisoners.

@Luis- The Peoples Temple was not what people usually think of as a fringe Christina cult- it combined elements of Christian practice with socialist and communist practice. Thus, it got a few notable left-wing politicians to praise it.

The evil conservative preacher was common in ’80’s fiction- think of Reverend Stryker in X-Men: GLMK. But that was still a few years away/

I don’t know about people, but _I_ certainly think of the People’s Temple as fringe Christianity (an admittedly varied and difficult to define group, not least due to variations from observer’s perspective).

Not everything that is worrisome in Christianity will resemble Westboro.

@Luis Dantas: I think that it’s generally true that superhero comics in the mid-1970s would have trouble conceptualizing a fringe Christian group. You’d be more likely to get a villain based loosely on the Unification Church or the Satanist Temple.

There were some villains of the fanatical reactionary revivalist type, though, such as Steve Gerber’s original version of the Foolkiller and the desperate, failing revival-tent preacher from one of Wolfman’s Tomb of Dracula stories who stupidly revives the vampiric Count in hopes of getting a “miracle” to present to his followers. And, of course, there’s Jim Starlin’s unsubtle satire of the Catholic Church in his Adam Warlock stories.

Reading your other comment, occurs to me that my earlier thought is basically Wolfman’s Brother Blood character from New Teen Titans…but that was in the 80s, per your first point.

@Michael: The People’s Temple is an odd case. Jim Jones seems to have been a psychopath who always wanted to gain total charismatic authority and abuse it. He figured out that left totalitarian thought with a veneer of Christianity would work especially well to do it.

But in pursuit of that, he supported integration in Indiana and some useful social programs in California. It was ultimately just a pathway to personal power, and Jones’s own preaching was duplicitous and terrifying, but he accidentally did some good things once or twice along the way. That was how he gulled so many people and took advantage of social turmoil to build his cult.

@Luis- This is tricky. The People’s Temple STARTED OUT as a member of the Disciples of Christ but by the early 1970s Jones’s beliefs were completely unrecognizable as anything resembling Christianity. in one interview Jones seemed to say he was an agnostic or atheist.

Some of Jones’s beliefs reflect left-wing beliefs. He argued that white supremacists would put people of color in concentration camps. He set up his compound in Guyana partly because it had a socialist government. He praised Lenin. Would you say that he reflects what’s worrisome in left-wing beliefs?

Wolfman definitely had enduring interest in voodoo since he also created Houngan in New Teen Titans a few years later, complete with over-the-top costume by George Perez. Something about portraying the same religion as evil more than once seems problematic, although Brother Blood does balance the scales there a little bit.

That’s a nice cover on this issue of Daredevil. It might have been mentioned here before, but I don’t think I knew Klaus Janson was already on the book at this point.

Daredevil will feature another story about voodoo and Haitian immigrants in about fifteen years with Daredevil #310-311. Sadly, Brother Zed doesn’t even get a mention.

@Thom H.: Ah, yes, Houngan, nobody’s favorite member of the Brotherhood of Evil. Weirdly, it’s not entirely clear he actually has magical powers; he seems to use technology instead.

@Chris V.: The Nameless One first showed up in issues #243 to #244 back during Anne Nocenti’s run, complete with flashbacks to his origins as a drug dealer in Haiti revived by a voodoo priestess named…sigh, Mambo.

In that story, the Nameless One is connected to Danny Guitar, who pretends to have voodoo powers to intimidate people…and is somehow not Brother Zed.

Then, in Daredevol #310, Mambo turns out to be the sister of Calypso, the villain from several terrible Spider-Man stories. So I guess in the Marvel Universe, Trinidadian Vodunu and Haitian Vodou are the same magical tradition, and their parents were really big fans of the musical traditions of the Antilles.

For the record, I know that “mambo” is also a term for a Vodou priestess, and both the dance music genre and the religiosu title come from a common African root word.

But Calypso definitely isn’t a religious title, and it comes from Greek mythology.

In any case, naming a Vodou practitioner “Mambo” is a bit like giving a Lutheran clergyman the name “Pastor.” And naming a Vodou priestess “Calypso” is like giving a Lutheran clergyman the name “Edda” because he’s vaguely Scandinavian.

Wait!

It turns out there’s a totally separate etymology for calypso music that comes from a traditional title for a singer and storyteller in Igbo and other African languages. I think it’s still kinda silly as the name for an exoticized evil sorceress character, though.

I forgot about the Nocenti story. Probably because the Nocenti run is my favourite DD era, and that story is Nocenti’s absolute worst, by far.

I guess DD was supposed to have a story involving “Voodoo” every decade, but the relaunch of the series messed it up. Now, I wonder if DD has been involved with the most number of Voodoo-themed Marvel superhero stories outside of Brother Voodoo or Simon Garth, themselves. Well, there’s also the Avengers villain Black Talon.

I think in the Marvel Universe, once you cross over into US territory, even if you’re not in Louisiana, if your religion is on some way based on West African Vodun, outside of just Haitian Vodou influence, it magically morphs into one size fits all Voodoo belief. It’s sort of like the discussion about the Wendigo curse and modern borders.

Honestly, as to whether or not Marvel, specifically, was ready to show villains representing fringe Christian groups in the 1970s, I think the answer was pretty clearly “no”, especially after the controversy that erupted when Jenny Blake tried to turn Ghost Rider into a Christian book.

I liked Houngan, as I’ve always been a fan when you do a mix of technology and magic (if you want to consider ?Voodoo as magic). But i’m also a B/C list villain mark, especially bad guy stables.

@Michael

Clearly you and I have somewhat divergent understandings of what fringe Christianity would be like and of what it would not be like.

Doubtless some of it is because I live in Brazil, where the right-wing turn of Christianity is a somewhat recent thing (and in large part a direct import from the USA).

But I suspect that I also simply have wider perceptions of what would count as Christianity. For decades now I perceive Christianity as a blanket term of sorts for a wide variety of movements with a perhaps even wider variety of reputations, deserved and otherwise.

It never occurred to me that someone might perceive left-wing tendencies as some sort of evidence of exclusion of Christian traits. I tend to focus on the theocentrism more than on specific political thoughts. I only assume that you see left-wing and Christianity as something of an odd mix because you present the contrast twice in two posts (and because there was an odd trend in the last fifteen years or so in Neo-charismatic Churches here in Brazil).

@Chris V: DD’s story with Voodoo and roughly similar activities (by comic book standards) is surprisingly long lasting and recurring. The Nameless One from #310 specifically goes back to #243-244, while Calypso (a Spider-Man character by way of Kraven) does… things that are sometimes presented as a form of Voodoo in Annual #9 as well as #310-311. Interestingly, Annual #9 brings back the original Marvel Zombie, Simon Garth, as Calypso’s unwilling tool against DD.

I’m surprised Marvel was able to get away with the Steve Gerber Son of Satan series, considering the controversy around Jesus appearing in Ghost Rider. The letter’s page would routinely have self-proclaimed members of the Church of Satan writing in to discuss the comic.

@Taibak

Yes, it sure feels reasonable that a publisher that feels that it is a bit too much to hint that Jesus might manifest among humans to help keep Satan at bay might not feel too confortable at pointing out that harmful fringe Christianity does exist.

@Thom H.- Voodoo had a negative reputation in the ’60s,’70s and ’80s. And while some of it was racism, part of it had to do with the Duvaliers in Haiti. The Duvaliers were horrible dictators. The Duvaliers’ secret police included voodoo priests and the elder Duvalier modeled himself after Baron Samedi. There were reports of attacks on voodoo priests in Haiti after the younger Duvalier was overthrown.

@Chris V

I assume that the Marvel editorial of the time compartimentalized things a bit. Not just mentally, but also from a marketing standpoint.

Son of Satan was clearly meant to be on the edgy side of their catalogue. Ghost Rider was slightly more mainstream, appearing on the cover of the Daredevil crossover to come, joining the Champions, and perhaps (I don’t know for a fact) making it to publicity items and merchandise where Daimon Hellstrom would not be appearing.

@Luis- I’m aware that there are left-wing forms of Christianity, for example, in the black community. My argument was that by the mid-1970s , the People’s Temple was closer to a non-Christian left-wing movement than a Christian movement. A left-wing black pastor might use the teachings of the prophets as an argument for social justice- he wouldn’t declare himself an atheist or an agnostic.

I think that a certain point you have to ask if most members of a religion would consider a certain group a part of their religion. If abuses were reported by a member of Jews for Jesus, most Jews would not consider that reflective of a larger problem within the Jewish community because most Jews consider Jews for Jesus Christians.

Similarly, by the late 1970s, I think most Christians wouldn’t recognize the ideology of the People’s Temple as Christian.

@Michael

I can honestly tell you that never before this exchange with you it even occurred to me that someone might conceivably see the People’s Temple as _not_ some form of fringe Christianity.

Sure, many Christians will deny it. That is nothing new. There are Catholics denying that the Pope is Catholic, even.

Messianic Christianity, which you call “Jews for Jesus”, is not really comparable. They specifically want to be perceived as fringe Judaism despite a blatant lack of interest in Judaism.

Had to check how long after Brother Voodoo was created did this story happen? Answer is 3 years or so. Which is also 3 years after Live and Let Die came out, for cultural context.

It is a little mysterious where the magic comes in with Houngan’s original gimmick of computerized voodoo dolls. Without going back and re-reading, I’m not sure what Wolfman intended in terms of a magic/science ratio for him. He’s definitely been shown to cast spells, though, as recently as a few years ago in Unstoppable Doom Patrol.

To clarify, I love every single member of the ’80s Brotherhood of Evil, even Warp and his stupid, stupid helmet. They actually scared me a little bit when they showed up and took down the Teen Titans. Wolfman and Perez gave them a distinctly creepy vibe.

I didn’t realize the political connections with the voodoo fascination of the ’70s/’80s. I do remember it being much more in popular culture when I was growing up, along with quicksand and the Bermuda Triangle. Interesting how cultural fears shift generationally.

Is anybody else rereading the title of this story — “Look Out, DD – Here Comes the Death-Man!” — and suddenly realizing that Brother Zed’s look may have been inspired by the similar “skleleton on black bodysuit” costume of 1960s Batman and Bat-Manga villain (Lord) Death-Man?

Since it’s not my area of study, I wonder why we had the lull of zombie stuff from the 40s with stuff like I walked with a zombie until the 70s revival. The whole conservative shift because of things like wertham and the code?

That said I encourage people to seek out, in an MST away the comedy called Zombies on Broadway, starring RKO’s version of Abbott and Costello (Clancy and brown) with Bela himself as the mad scientist. The zombie makeup must be seen to be believed.

@Mark Coale: It was the Comics Code.

Teh Code forbade all horror characters until the early 1970s. Then they amended it to allow horror characters if they had a “literary tradition” behind them.

Zombies did not have this tradition, unlike Frankenstein’s Monster, Dracula, and werewolves, so zombies were still banned. Marvel had to use the odd variant term “zuvembie” for a whole to sneak in something that didn’t violate the Comics Code. Marvel’s Tales of the Zombie was published as a bblack and white magazine, getting around the CCA entirely.

Later still, the Code’s prohibitions on horror characters were lifted almost entirely, so the zombies could be called zombies in the regular comics.

I meant in overall popular culture.

I had actually the Zeuvembie synonym on blue sky when I replied to Paul’s post for the thread. 🙂

Omar: Are you sure it was a categorical ban until the 70s? I mean, the X-Men fought Frankenstein’s monster back in 1967.

@Taibak

ROBOT Frankenstein’s Monster!

@Taiback: I was thinking about that one a bit. Frankenstein’s Monster is also shown in a flashback in an early Silver Surfer issue.

The original Code provision was “Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited.”

The Frankenstein’s Monster the X-Men fight is evcentually revealed to be an alien robot. And the one in Silver Surfer v.1 #7 is seen briefly in a film, its manner of creation unexplained. The Victor Frankenstein descendant int he story uses some kind of rays to turn a lump of clay into a duplicate Silver Surfer.

So Marvel got around the prohibition by avoiding the whole “made of dead bodies” angle entirely.

But now I’m left unsure how DC got away with the whole Benedict Arnold High School Faculty of Fear running gag from the Super-Hip stories in Arnold Drake’s Adventures of Bob Hope run, which had a werewolf, a vampire (named Van Pyre), and a character named Zombia Ghastly among others. I guess they were never confirmed as monsters? Or maybe the light humor element — or a love of Bob Hope — kept the CCA off their backs?

@Mark Coale: I wonder if it had something to do with the racial overtones of older zombie stories, which were starting to be rejected by the early 1960s. In the U.S., at least, Southern theaters and distributors also rejected works with multiracial casts in most instances, which would have put up a different kind of barrier by that point in time.

The big comeback of the zombie in film happens with Night of the Living Dead in 1968, which is really about what would have been called ghouls in older stories. It ended up divorcing the zombie entirely from the Haitian religion angle in most pop culture outside of the comics, which did bring back the Voudon angle and thereby gave us a houngan villain in a chicken costume.

@Taibak- the loophole they used was that the Frankenstein’s monster the X-Men fought was a robot that the book may or may not have been based on. When the real Frankenstein’s monster was introduced, I don’t think they ever explained why the robot resembled the monster.

As an irreligious person, it always struck me as kind of odd that comics regularly feature the devil, demons, Hell, all that, but almost never show any effects of God or angels or Heaven. And it’s not just comics, though there have been a few TV shows about angels. Why is Satan open to fiction, often completely divorced from religion, but proper angels or gods is seen as dangerously preachy or blasphemous?

Thor doesn’t count as a god.

@Si: There’s the 1990s Hellstorm series, which has assassin angels launcing a big scheme to destroy Hellstorm, since he’s effectively the Antichrist from their perspective. Heaven is shown as well, with Hellstorm at one point leading some sinners up to it, but it’s characterized somewhat negatively.

I can also think of two much earlier examples (not counting Jenny Blake’s aborted effort to have Jesus rescue Johnny Blaze from Hell). Curiously, both of them relate to Tomb of Dracula.

In the 1970s Dracula/Dr. Straneg crossover, Strange finally defeats Dracula and cures his own — and Wong’s — vampirism by invoking “Tetragrammarton” and “Jehovah,” essentially the Judaic deity (who’s also, therefore, the Christian diety according to Christians). Gene Colan draws this invoked power a big cross of light, decades before the Castlevania games.

The second comes in the latter issues of Tomb of Dracula itself, wherein Dracula takes charge fo a group of human Staanists, but both he and the Satanists find themselves unable to remove a painitng of Jesus from the deconsecrated church where they operate. A young woman in the cult named named Domini is married to Dracula, who is posing as Satan to keep charge fo them. But Domini seems to have gained religious faith after realizing that the cult is evil, and has a quiet, but overall good influence on Dracula.

Subsequently, Dracula’s newly born mortal, infant son, Janus is mortally wounded by a bullet aimed at Dracula (it’s complicated) is possessed by what is very strongly implied to be an angel, which then battles Dracula a few times under the name of the Golden Angel.

The angel-being leaves Janus in the final issue, restoring him to Domnini as a healthy, living infant, because Dracula has been destroyed by Quincy Harker (temporarily, as it turns out).

Many decades later, in the “Curse of the Mutants” stuff, an adult Janus is inexplicably a vampire in Dracula’s retinue, though he’s still portrayed as heroic.

I am curious if Paul will mention one of the dodgiest moments of DD #134. It’s a Torpedo team-up story against Chameleon, so it doesn’t really fit the motif of listing Daredevil rogues. Even if it provides more evidence that DD had been “borrowing” villains from Spider-Man fairly routinely long before the Kingpin. Just Kingpin, obviously, stuck and became more iconic with him.

But DD #134 has Matt decide to get himself out of having to either lie to Heather Glenn about why he has to leave or just telling her his secret identity by assaulting her and knocking her out. It’s a “nerve pinch,” like Mr. Spock would do, but that’s just a nicer version of a blackjack blow. Superman used to sporadically do that to Lois when writers were in a jam, but that was in the 1940s and 50s. This was 1976. It’s hard to pretend that was okay at that time, beyond the isolated, male-centric audience (and creative teams), I guess.

Heather Glenn does indeed stick around for about a decade and 4 more writers besides Wolfman, before she’s killed off by the last, Denny O’Neil (or rather, commits suicide). She gets a “sort of” cameo in the 2003 DD movie where a woman named “Heather” breaks up with Matt via an answering machine message.

Ah Heather Glenn. She hangs around in the background of the Frank Miller run and the subsequent era until her suicide right before Miller returns to the book for Born Again (though he writes or contributes in some way to a few issues before that).

I’ve always found it interesting that there’s never been any kind of interest in resurrecting either Heather or Karen Page. Admittedly, neither added that much to the book during the long stretches they were in it but still.

@Omar Karindu: One of the Satanists say they could remove it, but Dracula told them not to, allegedly because he wanted to show his power to it, but probably because he didn’t want to sem weak.

@Si

As Omar pointed out, there are sporadic uses of heavenly imagery. But there some good reasons why they are sparse.

1. Using those ideas in a plot is difficult unless the plot revolves around them. Which is a legitimate creative choice, of course.

2. Keeping narrative coherence may be difficult as well, particularly when there is a change of creative teams.

3. There is only so much that can be done without lasting repercussions that change the status quo. That may clash with the interest of comic publishers in keep publishing for years and decades.

Maybe it is just me, but I have a hard time imagining a storyline that makes strong use of supernatural forces and entities and yet goes on for decades. The closest that comes to mind might be “Dark Shadows”, but that is a probably a stretch in more ways than one.

4. It may become a public relations quagmire. All sorts of sensibilities are potentially offended when you use those sorts of plots. I don’t think there is any true solution to this dilemma beyond choosing a target audience and accepting that there is little chance of widening it.

He would then eventually bulk up, find space magic, and proceed to menace the Power Rangers.

…Wait, that’s the wrong Zedd.

@Luis Dantas: Also, it gets into uncomfortable questions of theodicy.

@AMRG- There are similar examples even later. In DeFalco’s Solo Avengers in 1987, DeFalco had Clint knock Bobbi out with a sleeping gas arrow so he could go fight Trick Shot. (Bobbi later punched Clint for this.) And in Roy Thomas’s Dr. Strange in 1991, Thomas had Dr. Strange knock Clea out with a sleeping spell so he could go fight the villain.

And then there are sibling examples. In Captain Britain 31, in 1977, by Gary Friedrich and Larry Lieber, Brian knocks Jamie out with a punch so he can go fight the villain. Jamie later becomes an insane supervillain- I wonder why?

@Si: There was a angel character in the ’90s Justice League: Zauriel. He was a guardian angel who chose to come to earth because he fell in love with the mortal woman he was watching over. when he was surprised, he exclaimed, “Great God!” (which I thought was a great joke on other superheroes’ “Great Scott!”/ “Suffering Sappho!”/ “X’Hal!” etc.) Other angels showed up in his introductory story (JLA 6-7). Not counting Vertigo titles, this was the most explicit acknowledgement of a Judeo-Christian theology in a major Big 2 series that I can recall.

Other examples I can thinbk of: The FF met “God” at least once during the Waid/Weiringo run, but it was Jack Kirby in a cutesy meta-gag. Al Ewing and Javier Rodriguez incorporated Kabbalistic ideas and imagery into their Defenders series. The Ostrander/Mandrake Spectre comics featured angels, heaven, and a version of God that turned out to be insane or something (I love that series, but haven’t reread it in awhile and recall not loving that particular story).

I haven’t read it yet, but I heard the most recent Azrael mini had a scary angel in it.

The Spectre is really an odd case though. He’s pretty much been portrayed as the wrath of God from day one, but he’s typically been depicted as brutal and terrifying. In terms of what he does, he’s really not too far removed from Ghost Rider.

Come to think of it, wasn’t there also a Ghost Rider story where he was revealed to be an angel?

God came to Spider-Man in Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa’s run on, what was it, Sensational?

I don’t remember how directly it was stated, but the intent was clear.

Over in DC, didn’t Peter David turn one of the Supergirls into a literal angel?

“Al Ewing and Javier Rodriguez incorporated Kabbalistic ideas and imagery into their Defenders series.”

The same is true of Ewing’s Immortal Hulk, which ultimately takes a turn into recapitulating the story of Job while avoiding any appearances by angels or other specifically named religious figures (by using Marvel’s cosmic ineffability The One Above All as a stand-in for the Abrahamic God and creating The One Below All to serve as the story’s Satan).

@Taibak: At least under Ostrander and Mandrake, The Spectre also went with a “the divine manifests as what you imagine the divine to be” idea, so there were characters in touch with the same general spiritual being who were decidedly not adherents to any of the Abrahamic faiths.

There’s a bunch of stuff in the Ostrander/Mandrake Spectre. IIRC, both the Spectre and Elcipso were the agent of god for things like Noah’s Ark and The Plagues of Egypt.

A lot of the early Sandman stuff involving Heaven and Hell was from before Vertigo.

Since I had just mentioned this on Blue sky earlier, a number of the Phantom Stranger’s origins from that issue of Secret Origins are Biblical.

Also, the Spear of Destiny, which originally appeared in Weird War Tales for those that didn’t know, has a long history in mainstream DCU history, including the origin of the JSA and the aforementioned Ostrander/Mandrake Spectre.

We mentioned JMDM last week and certainly his work is full of spirituality if not religiousity.

I notice no one’s bringing up Frank Castle’s “Angel Punisher” era.

In the Ostrander/Mandrake Spectre, I think Eclipso came first, as God’s Wrath. The Spectre came later as a Spirit of Vengeance (Eclipso accuses him of essentially stealing Eclipso’s old job.) Sometime later, I think after Jesus’ birth, is when God decides to combine the spirit with a human soul to, moderate it, maybe?

Of course, the Spectre is also revealed to be a demon or fallen angel that repented and asked to be forgiven, but has to accept being transformed into this spirit of vengeance, with no memory of its past existence.

I think the bit about God being insane was more about the Spectre (or Jim Corrigan’s) perception, as he grew increasingly frustrated with aspects of his existence and the task he’d been given. Throughout the arc he keeps telling people God’s missing and from all the other character’s reactions, the implication is he’s taking too narrow a view.

Of course, during one of the periods where Corrigan and the Spectre went nuts, they killed everyone in Count Vertigo’s homeland of Vlatava, except the count and the general he was fighting in a civil war, and the Archangel Michael later proclaims the act was “extreme and wholly without mercy, but not unjustified.” With that kind of judgement, the notion of God being nuts makes more sense.

Peter David combined the “Matrix” Supergirl, the one that was made of pink protoplasm or something, with a dying young woman (Linda Danvers) into an “earth-born angel,” one of three, ultimately. God (or some aspect of God) showed up frequently as a little kid with a baseball bat. I forget his name, Wally, maybe?

Wally, yes, @CalvinPitt.

A variant appeared in later issues of the sort-of-sequel series “Fallen Angel” when it switched publishers from DC to IDW. Except I don’t think this version of God as a Young Boy was actually named, and it used a tennis racket instead a baseball bat.

I think most people gloss over Punisher’s “Angel” period simply because it does not seem to work.

If only it could be tied to Romulus… (I kid! I kid!)