Daredevil Villains #47: Brother Zed

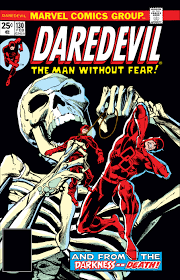

DAREDEVIL #130 (February 1976)

DAREDEVIL #130 (February 1976)

“Look Out, DD – Here Comes the Death-Man!”

Writer, editor: Marv Wolfman

Penciler: Bob Brown

Inker: Klaus Janson

Colourist: Michele Wolfman

Letterer: John Costanza

Once again, we’ve skipped some issues. Issues #126-127 are the debut of the Torpedo, a rookie rival superhero who does the obligatory misunderstanding-and-fight routine. He actually had some legs: he returns in issue #134 as a supporting character, then gets a try-out as a solo hero in Marvel Premiere , and finally winds up as a supporting character in Rom. But he’s not a villain, so he’s outside our remit. Issue #128 is another Death-Stalker story. And issue #129 brings back the Man-Bull.

In fact, focussing on the new villains will give us a rather unrepresentative view of Marv Wolfman’s run. He’s the first writer who seems to have looked at Daredevil’s pre-established rogue’s gallery and deemed them to be basically serviceable. There are only a handful of new villains in his run. And one of them is a very big name, but we’ll get to him.

It’s not that Wolfman didn’t create new characters for the book. He absolutely did, but they were mostly supporting characters. As well as the Torpedo, the issues we’ve skipped introduce Daredevil’s new love interest, Heather Glenn. We might not have much reason to talk about her here for a while, since her first major storyline involves the Purple Man, but she’s a major character who’ll stick around well into the 1980s. At this point, she’s a sort of prototype manic pixie dream girl.

Wolfman also brings in Blake Tower as the new DA, largely to take over Foggy’s plot advancement function once he left the job. And there’s a grumpy cop called Bert Rose who hates superheroes; he’s a recurring presence for a few years until he gets quietly dropped without ever having a storyline of his own.

Issue #130 also introduces the Storefront, Matt’s new operation giving free legal advice to the poor. Later issues will explain that Heather is an heiress and that daddy is paying for all this. We haven’t quite reached Daredevil as the protector of Hell’s Kitchen (the Storefront is on the lower east side, for one thing), but we’re much closer than before.

But we’re not here to talk about any of that. We’re here to talk about Brother Zed. And he hasn’t aged well.

Brother Zed is the houngan of a group of voodoo worshippers, all apparently Haitian immigrants. Zed appears to them as a burning skeleton. We first encounter him as he’s shaking down one of his worshippers for money, claiming that if she doesn’t pay up, the loa will take her son. She goes on the run and tries to get help, but her friends are all fellow worshippers who won’t break ranks with Zed. Eventually, Zed’s followers catch up with them and drag her off to Central Park, intending to sacrifice the boy, apparently so that Zed can teach everyone an important lesson about what happens if you don’t give him money.

Naturally, Daredevil happens to swing by, and he breaks up the human sacrifice. This being a 1976 voodoo story, Zed tries to kill Daredevil with a voodoo doll. But as soon as Daredevil gets close, he just kicks Zed in the face. The twist is that Zed is just a guy in a dodgy skeleton suit who has some low level hypnotic powers that make him look impressive to his followers. But as usual in this book, hypnosis doesn’t work on blind people, and so Daredevil isn’t even entirely sure why everyone else seems so impressed by this loser in a cheap Hallowe’en costume.

You will doubtless have noticed that this story features black people. Now, it’s 1976, and we’re not in the Silver Age any more. In some parts of the Marvel Universe, black people with actual dialogue are no longer a novelty. Luke Cage has been around since 1972; Storm debuted in 1975. But none of this had fed through to the pages of Daredevil, which was still overwhelmingly white at this point. The only significant non-white supporting character, Willie Lincoln, hadn’t appeared since issue #59.

Now, to be fair, crowds of bystanders were starting to get more diverse. And issue #127 had featured a fairly normal black family, living in low income housing in Westchester County. Their role was to have their house smashed up by the fight between Daredevil and the Torpedo, and then give both heroes a stern dressing down about the whole thing so that they can feel guilty about it. Technically, nothing about their role turns on them being black, but they’re clearly intended as a shorthand for the dignified urban poor.

And this is a story about voodoo.

To be fair, if the context included a wider range of black characters, this particular issue wouldn’t be so bad. In some ways, Zed’s worshippers do avoid cliche. The story pitches them as ordinary folk who are being taken advantage of. They aren’t straightforward zealots – Zed’s using illusion to exploit their religion. At its root, this is meant to be a story about a group of immigrants who are bound together by their shared religion, and the cynical priest who exploits their unity and culture by turning them into his cult.

There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with that. You could do it with a fringe Christian group and the plot would basically work. Maybe you could make an argument that voodoo just happens to be a more visual option. Viewed in this way, the biggest problem with the issue is the rather pat resolution after Zed’s defeat, where his followers take all of one page to realign their worldview after his illusions are exposed.

But the bottom line is still that black characters rarely get much to do much in mid-1970s Daredevil, this issue is a rare exception, and what do you know, they’re a gullible and easily manipulated bunch who are a danger to themselves and who spend their evenings decapitating chickens in Central Park. They get a lecture from Daredevil about responsibility. In the context of Wolfman’s run as a whole, this was probably intended as a more general “think for yourself” message – he’ll come back to that theme in a major Jester storyline about disinformation and deepfakes. But the way in which it’s played here doesn’t look good.

Brother Zed never returns, but he was clearly designed as a one-off villain. His routine is very specific to this story and this group of followers, so it doesn’t lend itself to repeat appearances. Still, it isn’t hard to imagine a version of this story where the voodoo was a bit less cliched, and the abuse of position angle came across more strongly. Zed himself isn’t a terrible villain; the problems stem more from the context in which he appears.

Mark, Omar: With the Spectre, it wasn’t just Ostrander and Mandrake’s take on the character. It goes back to Jerry Siegel’s original Golden Age version.

https://13thdimension.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/dead.jpg

I’m not convinced The Spectre would make a reasonable Daredevil villain. But I suppose it worked out ok for James Bond

I don’t think anyone mentioned Rick Veitch’s attempt to put JC in swamp thing 88 and the ensuing controversy.

I’m not quite sure why, but this talk about Abrahamic heavenly forces in comics reminds me of the prevalence of Symbiotes and Spirits of Vengeance in Marvel and of colored power sources in DC. Some ideas end up becoming part of an encompassing mythology in a shared universe.

For some reason (or perhaps luck of the draw) DC has a better track record at proposing and then letting go of those far reaching factors, as well as with making them coexist to some degree. The Lords of Chaos and Order, the Green and the Red and the Speed Force are still around (I think), but it looks like the Metagene no longer exists as such, while the Source and the Godwave are no longer nearly as ubiquotous as they once were. Maybe DC is just better able to cycle and compartimentalize its mythologies.

Mark: Nobody’s mentioned Dan DiDio making Judas Iscariot a canonical part of the DCU either.

Probably because we’d rather pretend that didn’t happen.

Didio’s retcon was foolish. Everyone knows, per Dracula 2000, that Judas Iscariot became Dracula.

@Taibak: There was also that brief, ridiculous attempt to identify Vandal Savage with the DCU version of the biblical Cain.

And, going the other way, the Cain and Abel from the old horror comics and the Dreaming seem to have been loosely redefined as some archetypal “first story of murder,” who human beings only see as anthropomorphic because of human perspective.

@Luis Dantas: The Lords of Chaos and Order were I think, tossed out formally when magic was recreated in the aftermath of Infinite Crisis. But its heyday had passed before then, when the late 1980s and early-to-mid 1990s buildup to a war between Chaos and Order just kinda…petered out.

No one talks about Kobra being an agent of the Lords of Chaos anymore, even though that played a significant role in some of the later issues of the original Suicide Squad.

I think the stuff that sticks at DC is the stuff that gives some common theme to a bunch of previously connected or similarly powered characters.

So the Speed Force is useful because it covers all of the speedster characters and the emotional spectrum connects all the Green Lantern-related characters who already had very similar construct-based powers.

At Marvel, the Darkforce is probably the best example, since it was originally just one character’s power — Darkstar’s — but gradually got connected to all the other “mysterious shadow energy” characters. Now it’s hard to remember that this was not the case from the start. Likewise, the whole “Web of Life” idea has hung on because it ties together all the spider-powered characters.

The stuff that doesn’t usually stick tends to be stuff meant to create a connection between a bunch of otherwise thematically unrelated characters. The metagene at DC and the more generalized animal-totem thing at Marvel from the JMS Spider-Man run both fell aside. I’ guess this is also what happened to seeing the Lords of Order and Chaos invoked for otherwise non-mystical characters over at DC.

One of the best returns of similar characters was when all the plant-related characters got tied together in the Black Orchid mini.

IIRC, Alec Holland, Pamela Isley and the guy who made the Black Orchids (Phil?) were all in Dr Jason Woodrue’s class in college, maybe at Gotham University.

Not to be pedantic or anything, but if we’re only up to issue 130, Matt’s current female love interest is not “Heather Glenn.” At this point, she is just “Heather.” No last name has been given as of yet.

Whew, I’m glad I avoided being pedantic!

“The stuff that doesn’t usually stick tends to be stuff meant to create a connection between a bunch of otherwise thematically unrelated characters. The metagene at DC and the more generalized animal-totem thing at Marvel from the JMS Spider-Man run both fell aside.”

Or Chuck Austin’s plan to sort mutants into bloodlines like angelic and lupine, which was never fully realized and now lives only in infamy.