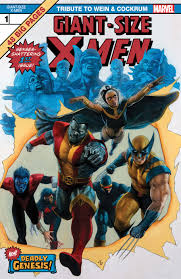

Giant-Size X-Men: Tribute to Wein & Cockrum

GIANT-SIZE X-MEN: TRIBUTE TO WEIN & COCKRUM

“Second Genesis”

by Len Wein and… well, about 60 names would be listed here.

This is certainly unusual. It’s a remake of Giant-Size X-Men #1, using the original script, but with modern artists doing a page each. I’ll be honest – the main reason I bought this was just in case they sneaked in something significant in the art. They don’t. It’s exactly what it’s promoted as: a straight cover version of “Second Genesis”.

It goes without saying that Giant-Size X-Men #1, now 45 years old, is one of the most significant single issues in X-Men history. Most people with a vague interest in the franchise have read it (and needless to say, it’s available on Marvel Unlimited). It’s the issue that relaunched the series after several years in reprint, and it’s the introduction of Storm, Colossus, Nightcrawler and Thunderbird, as well as the point where Wolverine and Banshee join the team. Len Wein didn’t stick around beyond this point, which Chris Claremont swiftly taking over – but Dave Cockrum hung around for quite some time, which gives it more sense of unity with the run that follows.

So sure, it’s important. But is it any good? After all, 1963’s X-Men #1 is important, but it’s hardly Lee and Kirby’s best work. It’s not even close to being their best issue of X-Men. And Len Wein only got one shot.

The original Giant-Size X-Men #1 is a mixed bag. It opens with an extended sequence of Professor X gathering his new team, all of whom get their own recruitment scene. Then it has to bring them together as a group, and put them together with Cyclops. And then it has to send them off on their first group adventure, to rescue the previous X-Men team from Krakoa the Living Island. It has an awful lot of ground to cover.

The battle with Krakoa is the book’s weak spot. Krakoa is a gimmick monster villain, and he has no particular resonance with the X-Men. It’s a bit of a giveaway that in the decades that followed, a period when many writers were obsessed with referencing old continuity, few people felt inspired to do anything with Krakoa. You wish there was a story at the heart of it that tied more closely to the X-Men.

But what Giant-Size does well is to introduce a large number of characters in a short period of time, give them all their day in the sun, and then use the Krakoa scenes to sell you on the idea that watching these guys as a team sounds like fun. Dave Cockrum has to cram a vast amount of action into 36 pages and he keeps it flowing dynamically. His character work helps to round out the new cast. And yes, it’s not a seamless team dynamic in the first issue – Sunfire, Thunderbird and Wolverine are all playing the role of team grump, and you can see why two of them were swiftly jettisoned – but it’s a good first issue when it comes to selling the series.

So… why do we need this? If you were being snarky, you might wonder whether the best way of paying tribute to Dave Cockrum was to remake one of his best known comics without the Dave Cockrum. But we’re in the territory of the tribute covers album here, not something you often see in comics. And while Cockrum’s art isn’t on the page, his presence is there.

That’s a mixed blessing. In theory, the idea of getting different creators to interpret the story is quite interesting. The problem is that they want to stick to Len Wein’s original script, and so there’s little scope for serious departures in pacing or layout. The scope isn’t there for artists to go crazy and reinvent a scene from scratch, or to interpret it loosely. Besides, Giant-Size is a dense book by modern standards, often running at 6-8 panels a page, so if you’re doing it page for page, you’re not really going to get a modern artist’s interpretation of the same story. It winds up tied closely to the choices that were originally made.

So if you read it side by side with the original, you’ll find that the vast majority of it is just a panel for panel rendition of the original. Many of the most striking differences come from the use of subtler modern colouring (often also credited to the page artist). It often deviates quite drastically from the original, and accounts for much of the change of mood.

It’s somewhat interesting to spot the individual panels which artists chose to change or tweak – Marguerite Sauvage gives much more prominence to Wolverine popping his claws for the first time, which is clearly the right choice in hindsight. Carmen Carnero and David Curiel seem not to have got the memo about using the original layouts, and deviate wildly for a looser sequence that abandons conventional panel borders – but that’s a sensible choice, since it’s the locals coming to worship Storm, and it could use a bit more mysticism to it. Bernard Chang drastically reworks his page too, to give Sunfire a more striking debut – it’s a particularly tricky page to work with since it features the tail end of one scene, a mere two panels for Sunfire’s intro, and the start of another scene.

The brief scene in Colossus’ family home is shown from slightly different angles so as to show more of the decor and better establish the location. Thunderbird’s buffalo chasing sequence is reworked in horizontal panels that look rather better to modern eyes. Leinil Francis Yu sticks to the original panel layout on his page but frames almost every panel differently, following the brief while trying to find his own angle on it. The giant crabs on Krakoa are given a bit more spotlight. Krakoa’s emergence is done in a more modern style as well, shifting to a splash page with inset panels – and yes, the original page does seem a bit staid in 2020.

But the points of interest are on that sort of level. It’s unlikely anyone would choose to read this over the original, because even though the individual pages are of a high standard, the very nature of jam issues makes the book uneven. It’s an intriguing curio and worth a look if you have the chance to compare them side by side, but it’s a little too faithful to the original to allow the impressive range of artists to fully bring out their own approach to the scenes.

It’s an interesting idea for a book, at least. Sometimes, on a project like this, you need to do it to figure out it’s not worth doing.

I enjoyed it for what it was getting to see some big name artists basically do a jam book.

I really like the concept of books like this in theory. The big problem is when I don’t know half the artists involved (or more). Anthologies are better for introducing new (or relatively unknown) artists, but this doesn’t give me a good sense of the style and strengths. It’s only useful for those I’m familiar with.

Perhaps reworking the whole thing as a modern update graphic novel would have been a better (but much more expensive) option.

> …you might wonder whether the best way of paying tribute to Dave Cockrum was to remake one of his best known comics without the Dave Cockrum

Yeah, this is where I am on this. I flicked through it and literally didn’t see the point beyond shovelware.

Some sort of modern remake could go either way, but this isn’t it.

I enjoyed looking at this, but can you really read it? The art changes from page to page can be really jarring- especially in Thunderbird’s introduction. I was excited to see some artist’s pages, and some others not so much. I think following the original layout was optional, and that made it seem less cohesive as a story also. All in all, it’s an interesting rehash of a story Marvel keeps going back to, and one that wouldn’t really be that great if not for the introduction of so many beloved characters.

Some items do seem as if the real goal in publishing them is as part of a research project into the completism of the collector mentality.

I’ve always liked the Classic X-Men #1 remix of this story better than the original anyway.

There are a few changes to the script. Let’s just say there are certain changes in dialogue that describes or refers to Sunfire and Thunderbird, since the originally used terms are no longer acceptable. Minor, but changes.

[I]Krakoa is a gimmick monster villain, and he has no particular resonance with the X-Men. … You wish there was a story at the heart of it that tied more closely to the X-Men.[/i]

In defense of Wein, the X-Men had no identity at the time, which is why it was a failed property. The superhero school theme was never well developed after Stan left the book. The allegory for oppressed minorities was also largely undeveloped. And of course the team of international superheroes angle was introduced here. It would be Claremont’s focus for the first half-dozen years or so, but Wein was setting the stage.

True, the angle in 1975 seems to have been “heroes from around the world” – but Krakoa doesn’t resonate with that either. It belongs in an “exploring the weird and unknown” book, I think – Fantastic Four or maybe even Incredible Hulk.

I quite liked the IDEA of this, but from what I’ve seen of it, it doesn’t have enough really good artists to get me to buy it (not that surprising, as last time I was able to look through a range of Marvel titles on the shelf I was quite disappointed with the overall range of art). I’d have bought it if it had just 4 of the better artists doing a whole chapter each.

> There are a few changes to the script. Let’s just say there are certain changes in dialogue that describes or refers to Sunfire and Thunderbird, since the originally used terms are no longer acceptable. Minor, but changes.

Also, Professor X.

[…] Paul O’Brien reviews the curious exquisite corpse of Giant Size X-Men: Tribute to Wein and Cockrum. […]

Tossing in a pedantic point here: Wein plotted issues 94-95 as well. This is of interest because of something Wein discussed a few years later: the original idea was to reintroduce X-Men as a quarterly double-size comic, and issues 94-95 were plotted as GIANT SIZED #2. That’s one of the reasons it ends with Thunderbird’s death–Wein wanted a shocking conclusion to bring readers back 3 months later. But for various reasons they decided to go with a standard monthly book, and Wein handled it off to Claremont to let it sink or swim.

I’ve said before that Wein deserves a heaping load of credit for trying to create a multi-ethnic, international team; a lot of opprobrium for doing it so clumsily–the Black woman is a naked jungle goddess! the Soviet loves his tractor almost as much as his sister! the Irishman loves bluegrass and drinks! the Indian hates the White Man!; and then a lot of credit for handing the book off to someone who would treat it with more attention than he could.

That is one way of looking at it, Kevin.

For all I know it is a fair and accurate way of putting it, even, and it may well be that Claremont was the best choice available at the time.

All the same, Claremont’s strengths as a writer are overall slanted much more towards concept than towards stellar implementation, and I think that he realized that to some degree even back in the day. He did not really do much with the foreign backgrounds of the characters that he inherited from Len Wein, nor was he particularly skillful at handling his own in early New Mutants or during the Australian Outbacks period. Other than the Moses Magnum in Japan story of Uncanny #118 or so, I don’t think he even attempted to portray other countries with any degree of nuance or local color. He pushed the envelope in creative ways, but the implementation was usually so crude that he ended up glossing over or retconning much of it.

Truth be told, Claremont’s characterization work is often lousy. To his credit, he tried hard to become better at character writing, so much so that we could not help but notice when he failed. 1979 Marvel did not necessarily have enough writers with better grasp of that admittedly challenging ability. All the same, it is still an aspect of his writing that is both salient and unsatisfying.

You have to remember that Claremont was a pretty new writer to comics at that time.

He didn’t have a lot of prior series that allowed readers to really grasp what strengths Claremont had as a writer.

I know that Claremont was influenced by the Thomas/Adams X-Men run, but I think when Claremont took over on X-Men it was just another assignment for him.

He most likely got (or took) the job because he didn’t really have any ongoing series he was writing.

He probably expected he’d end up leaving the book after a few years, like he did with Iron Fist or Marvel Team-Up.

I don’t think he’d ever imagine that he would fall in love with those characters.

From what I understand, Wein decided to drop X-Men because he was writing too many Marvel books a month.

I’m not sure if he decided he couldn’t keep up with the schedule or if Marvel editorial decided he was writing too many books. Either way, Wein decided to keep writing Brother Voodoo instead of X-Men.

Marvel’s writers were mostly still writing in the house-style at that time anyway. Most of them were trying to write as closely to Stan Lee as possible.

There were a few writers whose style stood out working for “mainstream” comics at that point.

Claremont was as good as anyone, really.

Wein’s multi-ethnic portrayal on X-Men was usually stereotypical.

(Let’s not also forget ignorant peasants chasing Nightcrawler with pitchforks and torches too.)

Claremont’s portrayal of different cultures was mainly slipping in a stereotypical line of dialogue.

“By the goddess, isn’t that true?”

“Da. It is true.”

Just the fact that Piotr was portrayed as a sympathetic Russian character during the Cold War was quite progressive though.

It wasn’t totally unique for Marvel.

Claremont’s Japan was always pretty stereotypical too. It looked like Japan was stuck in the feudal era, even though it was nearly the 1980s when he was writing that story.

Meanwhile, most popular culture has moved on to portray Japan as similar to Cyberpunk aesthetics by that point.

I’d like to say that as a kid reading a comic like those early issues, stereotypes were kind of informative. Giant-Size was where I learned there was such a thing as a Soviet collective farm.