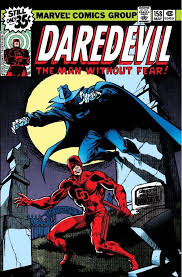

Daredevil Villains #52: The Ani-Men II

DAREDEVIL #157-158 (March-May 1979)

DAREDEVIL #157-158 (March-May 1979)

“The Ungrateful Dead” / “A Grave Mistake”

Writers: Roger McKenzie (#157-158) with Mary Jo Duffy (#157)

Pencillers: Gene Colan (#157) and Frank Miller (#158)

Inker: Klaus Janson

Colourist: Glynis Wein (#157) and George Roussos (#158)

Letterer: Joe Rosen

Editor: Al Milgrom

The second iteration of the Ani-Men only just about merit inclusion in this feature. They’re supporting players in the a Death-Stalker story, and a retread of an idea from the 1960s. But they scrape their way in because the second part is the debut of Frank Miller on art – and because there are only two real candidates for inclusion the whole Roger McKenzie run.

McKenzie takes over with issue #151, and his run offers the Purple Man (#151 and #154), Death-Stalker (#152 and #155-158), Mr Hyde and the Cobra (#153), Bullseye (#159-161) and guest villain Dr Octopus (#165-166). Issue #162 is a fill-in. Issue #163 has no villain – the Hulk guest stars to serve as the antagonist. And issue #164 is mostly a recap of Daredevil’s origin story. And that’s it. That’s the whole run. Bear in mind that the book is bimonthly at this point, so that’s two years of mostly retread villains.

This run does introduce Ben Urich, a genuinely major character who debuts in issue #153. He spends this run figuring out Daredevil’s dual identity and then deciding to keep it secret anyway. The run also introduces Becky Blake, a wheelchair-using lawyer, who promptly disappears into the background.

Roger McKenzie’s run inevitably suffers by comparison with the immediately following run by Frank Miller as writer/artist. That run is a landmark of early 1980s comics and would put anything in its shadow. But McKenzie’s run isn’t that great compared with what came before it, either. It’s never especially bad, but it’s highly formulaic. It could also have stood to pick up the pace: even though the Purple Man story had been running for ages by the time he took over the book, it still drones on for another year. Things improve once Miller settles in as artist, since the simple plots at least left plenty of space for Miller to do his thing. But you can see why Miller thought he could do better.

Let’s talk about the Ani-Men issues, though. They tie up the mystery of Death-Stalker, the (literally) shadowy villain that Steve Gerber introduced in issue #113. Some hints had previously been dropped about Death-Stalker wanting revenge on Daredevil, and it seems that Wolfman already had in mind that Death-Stalker would be the Exterminator, who had fought Daredevil back in issues #39-41 and seemingly died when some Kirbytech exploded. The main purpose of this story is to confirm who Death-Stalker is, and then write him out.

To be honest, it’s not obvious why he was written out. He’d worked well enough to make repeated appearances, and it’s not like the Daredevil rogues’ gallery of 1979 had many better options.

By issue #157, Daredevil has already been fighting the Death-Stalker. The Black Widow is back again, trying to shoulder aside Heather Glenn and reclaim her position in the supporting cast. This leads to Matt and the now-quite-extensive supporting cast (Foggy, Debbie, Heather, Becky and Natasha) gathering at Matt’s office so that Heather and Natasha can squabble over him. The resulting social awkwardness is interrupted by the new Ani-Men bursting through the window, and declaring that they’ve come for Matt Murdock.

They look the same as ever: animal costumes, enormous headphones and little boxes on their chests. In the original Ani-Men story, this technology played into a gimmick where they were being remote-controlled by their boss with clunky sixties technology. Their boss, the Organizer, intended them more to be fake villains that his political party could “defeat” – so there was an element of them being intentionally a bit sub-par. That aspect had faded away by the time they became the Exterminator’s henchmen. By 1978, the Ani-Men are simply oddball gimmick villains and their dated equipment is just a costume feature.

Why bring them back here? Well, as part of his bid for revenge, Death-Stalker wants to re-enact the time he fought Daredevil as the Exterminator. It turns out that the explosion didn’t kill him, but left him stuck out of phase with reality. Since the Exterminator had the Ani-Men as henchmen in the original story, Death-Stalker needs them for his amateur dramatics. But the Ani-Men had only just been killed off over in Iron Man, and so we end up with this: a group of random thugs wearing the Ani-Men costumes in order to plug the gap.

The new Ani-Men are more aggressive than their predecessors, no doubt in part because standards had changed since the 60s. In issue #157, Gene Colan has them battering Natasha. But issue #158 sees Frank Miller take over the story in progress. He plays it safe on his first issue – it’s much busier and more contained than Colan, but doesn’t push the boundaries. Marvel already knew what they had with Miller – the credits correctly proclaim him a “truly great new artist” who “will explode upon the Marvel scene like a bombshell” – but this first issue isn’t the best example of his inventiveness. Also, it features Death-Stalker and the Ani-Men, all of whom were a better fit for Colan’s more traditional melodramatics.

The Ani-Men abduct Matt, who can’t fight back without giving away his secret identity. The new Bird-Man gets caught, but the other Ani-Men abandon him so that they can split the money two ways instead of three. Matt tries to persuade the remaining duo that Death-Stalker will betray them, but they don’t believe him. And we wind up at a graveyard for Death-Stalker’s show. There’s an open grave and a gravestone with Matt’s name on it. (“Matthew Michael Murdock – may he burn in hell”.) Death-Stalker recounts his origin story, then casually murders the Ani-Men while they’re busy counting their money. And that was the Ani-Men. Thanks for coming.

The rest of the issue features a seven-page fight scene between Daredevil and Death-Stalker, ending when Death-Stalker turns solid in order to attack Daredevil, only to get stuck halfway through a gravestone and die.

Ape-Man and Cat-Man, of course, stay dead. The new Bird-Man gets out of the story alive, but he doesn’t appear again until 1986, when he’s among the horde of Z-listers killed by Scourge in Captain America #319. He was also among the dead Z-listers raised from the dead in Rick Remender’s Punisher in 2009. But the new Ani-Men only exist as characters because McKenzie wanted to do a callback to the Exterminator story, and the originals were dead – there’s nothing more to them than that.

“it seems that Wolfman already had in mind that Death-Stalker would be the Exterminator, who had fought Daredevil back in issues #39-41 and seemingly died when some Kirbytech exploded.”

This is complicated. Matt deliberately destroys the Kirbytech to (a) free Debbie Harris from another dimension and (b) fake the death of Daredevil since Foggy and Karen “know” that Mike Murdock is Daredevil. As Omar has pointed out, Foggy’s dialogue at the end of the issue is apparently meant to imply that the Exterminator is merely unconscious- after all, Stan would not have Matt cause the death of a villain largely to fake his own death. But McKenzie writes this issue as if the Exterminator has been believed dead for years.

“The run also introduces Becky Blake, a wheelchair-using lawyer, who promptly disappears into the background.”

Becky stays on the book relatively long, until issue 226. She disappears after Born Again because Matt was no longer practicing law. She’s later brought back during Brubaker’s run.

And she refuses to forgive Matt for his actions while possessed by the Beast during Diggle’s run. She and Dr. Strange’s secretary Sara Wolfe are examples of 80s female supporting characters who seemed like they would permanent features of the hero’s life but were forgotten about by later writers.

I can’t figure out why McKenzie let Bird-Man live after this issue while killing the other Ani-Men. No other writer could figure out what to do with him on his own so it’s no surprise that he was killed off in his next appearance.

Bird-Man was turned into an actual bird-man when the Hood brought him back from the dead. And he survived the Punisher issues. Not that it made any difference, since his only appearance since then was as a face in the crowd among many villains in an Iron Man issue.

So we are about to get two very important introductions, obviously Elektra will be covered but will you be doing fisk other then as part of her story has he is an established character.

I quite liked the retro look of the ani men the headphones make the recognisable so helpful them stand out.

Elektra probably won’t be getting covered as she was a supporting character rather than a villain. Characters like the Human Torpedo and Paladin didn’t get covered because they ended up being treated as heroic figures rather than DD villains.

I’m sure Kingpin will be getting his own feature, as he becomes DD’s arch-nemesis, as big a part of the DD mythos as Bullseye. Plus, if a lower-tier recurring DD villain like Electro (who was introduced in Amazing Spider-Man) gets covered, then surely Kingpin is a lock.

That’s if this series will be continuing. I understood it as only running up to Miller taking over, as it was being used for Paul to introduce himself to DD’s lesser-known history. I may be mistaken though. Is this series meant to run until present-day DD?

If this does continue into the Miller run, Punisher should also be considered a villain at this point. I would personally argue that’s always the case, actually, but in particular here.

@Michael:

The way the story runs, Bird Man survives because Black Widow (and Becky, curiously enough) tag-team to put him down before he can escape with Cat Man and Ape Man, who can’t be bothered to attempt to help him.

It is a bit of instant characterization, as we realize that Becky has hidden depths (an important detail for such a new character); that Natasha has not lost her touch just because the plot demands that Matt will fight alone; and that these costumed criminals are indeed bad people, albeit in varying degrees (Cat Man is callous and greedy, Ape Man is a bit too much of a follower for his own good, Bird Man is naive about the degree of loyalty of his erstwhile teammates) so that we don’t feel too sad when Death-Stalker comes with barely disguised threats and indeed kills the two who actually returned.

It is all used for good effect, since Death-Stalker does achieve a terrible death just a few pages later out of, basically, being too full of irrational hatred. So our hero ends up surrounded by deaths that he tried to avoid and failed to, thereby earning his credit as a genuine tragic heroic figure. For good measure, all this happens while he is oblivious to Becky’s feelings for him and also spared from actually taking a stance about Heather and Natasha.

Me, I am something of a fan of Roger McKenzie’s runs, both here and in Captain America at roughly the same time. He strikes me as more nuanced, less erratic and less predictable than Marv Wolfman, more passionate than Jim Shooter, and barely less skilled than Frank Miller, if at all.

His plots are considerably more formulaic and less daring and visceral than Miller’s, to be sure, but he shows a lot more skill at working with what he is given and building an engaging story around a plot that gives readers room to write in and tell how they want things to develop. I have not researched it, but he appears to be someone well trained to take into account the requirements of DC and Marvel in the 1970s, when solo books just were not expected to have too much impact in the shared continuity.

Meanwhile, it may be the “The Dark Knight Returns” reader in me speaking, but I find Frank Miller _way_ over-rated as a writer. For Daredevil specifically he was however quite the breath of fresh air. I just don’t think that McKenzie was much worse, and I suspect that Miller benefitted imensely from simply being a newbie writer given the chance to write a character whose book was already on the edge of cancellation. He took liberties that might have been forbidden him under less extreme circunstances, or if he already had a reputation as a writer that he wanted to preserve.

To a degree it is a situation that reminds me of Jim Starlin taking over Iron Man, Captain Marvel or Warlock. The perception of creative dead ends made it possible for the new kids on the block to dare a lot more than usual and reap the results – good or bad – also to a greater extent than usual. There is a bit of that in 1970s X-Men under Len Wein and early Chris Claremont, of course.

Starlin never really took over on Iron Man. He was there for #55 (introduction of Thanos, which was barely an Iron Man story), then did the artwork on #56, while Gerber wrote the issue. Starlin was supposed to stick around on art with Gerber on Iron Man, but Stan Lee hated Gerber’s first Iron Man issue and wanted him off the book. I’m not sure what happened with Starlin on art. If he didn’t want to work on the book without Gerber, or if he was just busy with his own creations.

I agree about McKenzie. I see people say they were unimpressed with McKenzie’s work on DD and Cap. I wonder if it’s because he took over both books at a real down point, then more prominent creators followed on each book.

DD was on the verge of cancellation when McKenzie picked up for Shooter, then got taken off writing the book for Miller. Cap was a complete mess when McKenzie took over. Thomas’ issues screwed up Steve Rogers. Steve Gerber, of all people, was given the job of trying to fix the mess (Gerber was, without a doubt, the best writer Marvel had at the time, but he wasn’t the writer to iron out continuity issues), but he quit almost immediately. I didn’t hate Gerber’s ret-con of Rogers’ origin either. Regardless, McKenzie was left to pick up the pieces before Stern/Byrne had a lauded run.

Personally, I enjoyed McKenzie’s run on Cap (and definitely the DeMatteis run which followed) more than the Stern/Byrne issues.

Getting back to DD, I found the stretch of issues with the Hulk and Ben Urich to be truly good DD stories. In many ways, it was the high point of the series until Miller’s writing.

The problem with Gerber’s retcon of Steve’s origin was twofold. First, Gerber tried to claim that Steve only became Captain America because of his brother’s death at Pearl Harbor. But Steve was well established at that point as having been Cap before Pearl Harbor.

Second, Gerber tried to establish that Steve was from a middle-class family and was at odds with his father because he was a pacifist. This seemed to be an attempt to shoehorn onto Cap an origin that Gerber thought ’70s readers would relate to. And Steve’s reaction upon hearing the Skull’s origin (“my past isn’t too pretty either”) implied that he could relate to the Skull’s stories of growing up poor. Just about every writer since DeMatteis has played up that Steve and the Skull both grew up poor, and lacking in positive male models.

McKenzie’s run on Captain America was weird in that Sharon Carter seems to have died, but we only get confirmation in issue 237, which was scripted by McKenzie but plotted by Claremont. I’m not sure if McKenzie originally intended Sharon to die.

Roger McKenzie also had a really brief, but really good, run on Ghost Rider that was responsible for turning the book away from its superhero trappings and into a darker, more horror-oriented series.

Death-Stalker gets high marks for me based on his design and power alone. I’d love for a modern DD writer to find a way to revamp him.

My assumption is that Death-Stalker gets killed off here for two reasons: first, they just wanted to be rid of him entirely given how long he’d been popping up to do arbitrary things.

And second, once you reveal who and what he is, the spooky mystique and the mystery plot elements are gone, leaving him as little more than a standard-issue vengeance-seeker.

As to Roger McKenzie, I generally find him a solid-enough plotter and a thoroughly average scripter. But it’s hard to say where he would’ve gone had he gotten longer runs on some of these titles, once he’d cleared out the deadwood plots. His Daredevil run seems to spend its first three arcs writing out some villains McKenzie doesn’t want to use: the Purple Man and Death-Stalker bot seem to die, and Bullseye has a total mental collapse when he actually has to fight Daredevil instead of hiding behind Eric Slaughter’s murder-for-hire gang.

It’s oly after this that the innovations come in: Ben Urivh’s decision about DD”s secret identity, for instance, or the Gladiator getting mental health treatment and retiring from villainy. (Even that reads like putting an old villain out to pasture.)

But McKenzie is off the book before he can do much more than that stuff, along with the Hulk story that redoes the Daredevil vs. Sub-Mariner story from the Wally Wood era and a chapter of McKenzie’s running, multi-title plotline about Doctor Octopus trying to get indestructible arms. His other really good idea — Daredevil vs. the Punisher — gets delayed due to censorship issues, and it’s only executed after mIller has taken over the whole book.

His Captain America run likewise seems like a longer deck-clearing exercise, leavened with some recombined elements. One again, there’s a neo-Nazi menace, but this time it’s Doctor Faustus, not the Red Skull. And as in his Daredevil run, a once-fearsome, obsessive maniac villain psychologically collapses when he actually might have to fight the hero: this time it’s the Grand Director/50s Commie-Smasher Cap. The long-stagnated romance with Sharon Carter is summarily, brutally ended. That Dr. Octopus plot turns up for a later fill-in issue.

And McKenzie’s one really clever idea — Cap for President — is again taken up and executed by a more celebrated subsequent creative team.

So it’s the subsequent Stern/Byrne run that really creates a new, long-running status quote for Cap by introducing the Brooklyn Heights gang.

My sense is that McKenzie had some good ideas, but his pacing is a bit too slow and his scripting style was rather flat. Coupled with his being assigned to books that were stuck in ill-advised changes and long-term stagnation, he tended to get pushed off of titles before he could take a swing as some of his more innovative ideas. But, hey, he still got Ben Urich in there before he left, and that’s a hell of a big contribution.

And as for the Ani-Men II. They certainly existed, briefly. And no one’s ever really used the Ani-Men team as serious villains again. These days, they’re mostly a background gag.

As with almost every Marvel super-hero comic from 1961 until about 2000, I wonder how much of the plotting came from the writer and how much came from the penciller. McKenzie may have written better DD stories later in his run when Miller was the artist, or it could be Miller’s visual storytelling approaches and surface elements made the stories better. I’m sure it’s a combination of the two, I just think the artists should get more recognition for their contributions to the plotting.

Omar – McKenzie created the Brooklyn Heights gang (Josh, Mike, Anna), he simply didn’t create the most famous one – Bernie.

@Michael Hoskin: Thank you for the correction!

Anna Kappelbaum’s introduction — which also brings in Josh and Mike — is a particularly memorable story, too. Was Cap v. #237 the first time the book explicitly dealt with the death camps?

I believe there’s a gag in DEADPOOL #0, the Wizard exclusive, where the second Ani-Men get revived by Arnim Zola for Deadpool to crack wise about the Scourge!

These are the same Ani-Men who fought the X-Men after the relaunch, right?

If so, what happened to Dragonfly?

@Taibak: Those were the original Ani-Men, who Paul notes above had just recently been killed off in Iron Man v.1 #116.

As to Dragonfly, she was briefly seen in Uncanny X-Men v.1 #104, where it was shown that she’d managed to escape her cell on Muir Island(!) when Magneto was freed and de-aged by Eric the Red.

But then she vanished for many years. A Quasar story had her as one of the many minor, obscure characters who turned out to have been collected by the Stranger, and she presumably returned to Earth after that. She makes some very minor “face int he crowd” appearances as one of Superia’s Femizons in an infamous Captain America story from the later Gruenwald era.

There was also a Scott Lang Ant-Man story from an Iron Man Annual that gives her the real name Veronica Dultry and has her mutate into some kind of mindless insect-monster, which is held by Dragonfly’s sister and used to do terrible things until Ant-Man discovers what’s going on and puts a stop to it.

Other than that, Dragonfly has mostly been a crowd-filler in various stories, as when she turned up as part of the 25-member Masters of Evil back in Thunderbolts v.1 #24-5.

Grrrr…my memory is going. Dragonfly is not seen on Muir Island in <Uncanny v.1 #104, but her escape is noted.

Also, apparently her escape was intended to set her up to appear in a Dave Cockrum-created team of super-women called the Furies, at least according to the Marvel Universe Fandom site.

@Michael Hoskins, Omar- Captain America 237 has Claremont credited with the plot and McKenzie credited with the script. It’s anyone’s guess who created the Brooklyn Heights characters.

Well, I’ve reread the Roger McKenzie run of Captain America, and my take is that McKenzie had the same two problems he had on Daredevil:

1) He was tasked with bringing the book out of a long period of doldrums, but wasn’t on it long enough to fully get o his own stuff.

2) He seems to have had a lot of solid ideas for the character’s setup intermixed with some generic plotting and scripting, but his best ideas don’t seem to fully make it onto the page until he’s gone.

As Michael Hoskin points out above, McKenzie sets Steve Rogers up with his “freelance artist” job and co-creates the Brooklyn Heights gang, sans Bernie Rosenthal, in retrospect the most significant member. Steve’s freelance artist job is mostly used for comedy scenes with wacky clients or Peter Parker-esque “can’t do the job, must fight bad guys” sorts of scenes. We don’t get much sense of what Cap actually thinks about being an artist for a living.

But Anna Kappelbaum is the only one who gets much backstory before McKenzie’s off the book, and both of the stories focusing on her are entirely about the fact that she is a Holocaust survivor.

One is a flashback to Cap liberating the camp in which she’s held; the other is a sort of “Simon Wiesenthal vs. ODESSA” plot with some latter-day Fourth Reichers and a rushed idea about a Nazi doctor who’s apparently developed a conscience only to be killed by a Nazi hunter.

Josh Cooper is developed as Steve’s civilian best friend, but it falls to Peter B. Gills, in a fill-in between the McKenzie and Stern/Byrne runs, to reveal that Josh is a special education teacher. This is almost certainly an idea McKenzie had and that the editor handed on to Gillis, but MzKenzie never manages to get it onto the page himself. And Mike Farrell is probbaly meant to be a firefighter — he’s introduced rushing out of the building on his way to some unspecified emergency — but that, too, only gets introduced belatedly by Roger Stern and John Byrne.

As to the plots…McKenzie’s stories are, frankly, kind of generic. The National Foce plot, which is as much about clearing out the stagnant Sharon Carter romance as anything else, is a pretty superficial comment on neo-Fascism and interracial conflicts. As letter writers point out, having Dr. Faustus’s National Force appear mostly as the reusly o fhis mind-control gas means the story can’t say that much about actual prejudice. It’s not even clear if Faustus is himself a Nazi sympathizer or if this is just his idea of the best way to test his gas and take over the U.S.

The Black community that fights back in the story is likewise undermined as serious commentary: longtime minor villain Boss Morgan is their main representative, and he’s a hypocritical mobster. While he’s not faking his Black pride, unlike the earlier Harlem mobster villain Stone-Face, he has no answer when it’s pointed out that he’s only othered when white people victimize the community, as opposed to himself.

Captan America is briefly brainwashed into voicing support for the National Force on television, complete with a Nazi emblem painted on his shield. This seems to be cleared up almost instantly after the story ends.

Beyond that, there’s the Adonis plot, a generic “rich guy makes himself a monster seeking immortality, goes on a rampage” adventure that reads like it may have been an Annual story split across two issues.

McKenzie’s other really god idea — “Cap for President” — was rejected in its original form, then reworked by Stern and Byrne for their run, with Stern making sure Mckenzie and on Perlin got credit for the original idea.

All in all, then, it’s a pretty short transitional run, one that gets away from the stuff that had been holding the book back — Sharon Carter’s inconsistent and dull characterization, Cap constantly tied up with SHIELD, Steve Rogers as little more than Captain America without his costume — but it doesn’t really get anywhere beyond that.

Who knows where McKenzie might have gotten with the book in the end? But then one could say the same for his longer, steadier run on Daredevil, which also never fully got off the ground before Frank Miller took the whole thing over.

“But then one could say the same for his longer, steadier run on Daredevil, which also never fully got off the ground before Frank Miller took the whole thing over.”

I mean, he was on the book for over two years. If it didn’t get off the ground in that time, he’s doing something wrong.

Very true.

I think that McKenzie’s Daredevil and Captain America runs suggest that he pitched good ideas and supporting character concepts to his editors, only for his month-to-month writing to keep putting the good ideas off.

Ben Urich is set up, vanishes for six issues, and then vanishes again until well after McKenzie’s off the title. A fanatically anti-crime judge named Coffin gets a couple of scenes hinting at ominous developments, but nothing happens before McKenzie’s off the book.

This isn’t Claremont or Wolfman juggling lots of setups and subplots, letting some of it percolate in the background. The subplots and supporting cast just feel squeezed in. McKenzie’s multi-issue plots bog down because he mistakes bringing in additional, preexisting villains and new guest stars allies for amping up the scale and excitement.

And before Miller shows up with his Eisner-esque graphic style to convey a lot more story per page, McKenzie’s one- and two-parters seem very crowded, with character subplots squeezed in at the margins. On Captain America, McKenzie never gets that kind of artistic collaborator, so the pacing never improves.

It’s frustrating: there are clearly some promising ideas in there, but McKenzie’s plots and scripts seem to wallow in generic elements rather than advancing or, at times, even articulating the fresh, stronger material.