Daredevil Villains #62: The Congregation of Righteousness

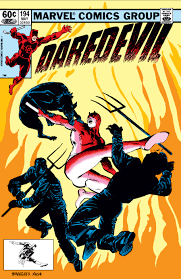

DAREDEVIL #194 (May 1983)

DAREDEVIL #194 (May 1983)

“Judgment”

Writer: Denny O’Neil

Artist: Klaus Janson

Letterer: Joe Rosen

Colourist: Glynis Wein

Editor: Linda Grant

Following Frank Miller on Daredevil is not an enviable task. After two quite decent fill-in stories, the man who takes on the assignment is the book’s editor Denny O’Neil – not so much because he wanted the job as because somebody had to do it, it would seem. He’ll be with us until issue #226, give or take a few fill-ins scattered along the way.

This issue doesn’t read like the start of a planned run, though. The next issue starts some actual storylines, with issue #200 looming on the horizon, but issue #194 this feels like it was intended as the book’s third consecutive fill-in. The editor credit tends to confirm that the book was playing for time at this point. Officially, Marvel didn’t have writer-editors in 1983, but they may have been paying lip service to that policy here. Linda Grant, credited as “guest editor” on this issue and “special editor” on the next, was not a full-fledged editor, but O’Neil’s own assistant. She remains the credited editor up to issue #200, after which the book is finally reassigned to a different office.

The Congregation of Righteousness are a bit of a borderline inclusion in this feature. “Judgment” is clearly a one-off story and the Congregations were never candidates to be recurring characters. But they’re not exactly generic either, and besides, it’s the first issue of a new writer. So let’s have a look at it.

Jeremiah Jenks grew up in a puritan religious sect, the Congregation of Righteousness, who reject all modern technology. They even take exception to drawing, so talented artist Jeremiah wound up killing his father in self-defence and running away. Jeremiah made a fortune using his artistic skills as a counterfeiter but still fundamentally subscribes to the Congregation’s religion. Now in old age and declining health, he wants to atone for his crimes by reconciling with the Congregation before he dies. As a first step, he’s tried to return to their traditional way of life, and part of that involves burning candles that he buys from a Congregation farm. Lots of candles. Tons of candles.

Since the Congregation will kill him if he shows up in person, Jeremiah hires Matt to speak to them on his behalf. So Matt and Foggy head up to the Congregation’s community in upstate New York.

The Conregation are quite obviously modelled on the Amish. Jeremiah even has two simply-dressed sons who show up in Manhattan in a horse and cart. But the story stresses that the Congregation are way more draconian, and are rumoured to kill and torture heretics. This is all a bit odd. While the Amish do shun excommunicated members (or at least some groups do), they’re hardly associated with extrajudicial killing – if anything, they’re generally perceived as harmless pacifists. Perhaps the story is just running with the idea that weird country folk are always a bit scary. Or maybe it’s just cranking up excommunication to the point where it can work in a superhero plot, but it’s not evident that the Amish become any more interesting for being made more like the Taliban.

Matt speaks to the Congregation’s elder, Nahum – Jeremiah’s own brother, though that point isn’t particularly stressed. Nahum tells Matt that Jeremiah was sentenced to death seventy years ago, and the decision is final. Rather than getting into the point about the Congregation doing extrajudicial killings – which, to be fair, probably wouldn’t be very persuasive – Matt instead tries to persuade Nahum that his religious beliefs are a bit extreme. Unsurprisingly, this prompts a rant about how the Congregation have no crime, violence or divorce. Except when they kill heretics.

Meanwhile, Jeremiah asks the Kingpin to arrange some security for him – presumably he thinks that Matt’s visit might prompt retribution. The Kingpin decides to go one better, and sends his henchmen to intimidate the Congregation into taking Jeremiah back. This is very helpful, because it provides some thugs for Matt to punch. After that’s finished with, Matt is thrown off the Congregation’s land.

At this point, Matt finally figures out that the Congregation is already killing Jeremiah by poisoning the candles. He races back to Jeremiah’s home just in time to save him – a remarkable bit of timing, considering how long Jeremiah has apparently been burning the things.

So far, all of this is perfectly fine, and Janson’s art is rather striking. But the story ends on a very weird note, as Jeremiah decides that to stop running from his past. He’s going to present himself to the Congregation, “and let them do as they will”. This makes sense in terms of Jeremiah’s world view, but Matt doesn’t even try to talk him out of it. Instead, Matt immediately accepts Jeremiah’s wishes, more or less congratulates him for taking responsibility for his actions, and lets him go on his way. Bye, Jeremiah! Good luck with being murdered!

You’d expect the ending here to be Jeremiah insisting on the sacrifice which he believes to be a necessary part of his atonement, and Matt either reluctantly deferring to his wishes or somehow being given the slip. It might simply be a case of the story running out of room, and not having enough space to let Matt properly argue the point. But it reads very strangely.

Religion will eventually become a major theme in Daredevil. But that hasn’t happened yet; in 1983, Daredevil is still a basically secular character, unless you count the mystical elements introduced by Frank Miller via Stick. And even there, Matt is a secular figure from outside Stick’s mystic tradition. This story might well have been a better fit for the later, more religious, Daredevil. He would more plausibly have respected Jeremiah following his beliefs to a suicidal conclusion – and he would have found more in the story to resonate with his own self-destructive tendencies. In 1983, Matt doesn’t yet bring that to the story; he’s simply playing a secular visitor to a fringe religious culture, and he’s much easier to swap out for other heroes.

But it’s not a bad issue – it’s just the third de facto fill-in story in a row. That must have left readers wondering what the post-Miller direction was, if there was one at all. The next issue will start to address that.

Maybe they could “do a Beast” and bring in a version of Hank from earlier in his timeline, pre-breakdown, but it would only be a matter of time before some writer decided to do a history-repeats-itself thing and have him strike out again.

Exactly, even if someone I’d trust with the character, like Ewing, revamped him, there will be whomever follows him.

@Mark Coale — I imagine it was no accident that you mentioned Al Ewing, since he did briefly touch back with Hank Pym in the extremely brief AVENGERS, INC. Thanks to various machinations in Ewing’s Ant-Man mini series, Hank revived from his merger with Ultron, but wound up aged in the process. He was still a bit batty, manipulating low level villains into defending against Ultron — which turned out to be correct. Hang did briefly meed Nadia Van Dyne, and they got along for a couple of pages. Nadia liked that Hank didn’t treat her like an infant and fully expected her to aid in the brains department or run with the rest of the spare Avengers in the series finale.

But, these days Ewing is splitting his time with DC, and while his Metamorpho got axed fast, they did trust him with Absolute Green Lantern. Between him and Kelly Thompson, DC’s trusted a few writers Marvel kept on the C-tier who turned out to do top 10-20 selling Absolute titles for them. It’s flash in the pan, sure, but Marvel never would have let either near Ultimate 2.0.

“…but I think people don’t talk about/acknowledge that first Yellowjacket story because it’s old and really bad.”

I really don’t think that has anything to do with it. It’s not like Avengers #213 still carries that new comic book smell either. And good story or bad, the Yellowjacket intro story is at least notable. Your average longtime Avengers fan is almost certainly familiar with it.

Besides, the story was referenced again by Busiek when he had Janet regretfully acknowledge that she had taken advantage of Hank while he was clearly ill, and that didn’t stick to her either. That handbook entry Michael referred to actually speaks to my point. Whoever wrote that particular accounting of events clearly wanted to let Janet off the hook to the point of blatantly making shit up. Roy Thomas acknowledged that Janet manipulated Hank into marrying her. In fact, that Goliath costume that Clint wore when he adopted the Goliath identity was intended for Hank; an apology gift for tricking him (I imagine she had a hard time finding an appropriate card to go with it. I can’t say I’ve ever seen a section for “Apologies for taking advantage of your schizophrenic episode to rope you into making a lifetime commitment” in all the times I’ve ever shopped for a greeting card).

I think the difference is that Avengers v.1 #59-60 reads like Silver Age gimmick storytelling, with chemicals that cause someone to develop a second personality and big “shock” reveal at the end of each issue.

Whattaya mean Jan is going to marry this guy who showed up boasting that he killed Hank?!? Whattaya mean it was really Hank all along, just with some kind of split personality caused by a lab accident?!?

In comparison, Avengers v.1 #213 is written as the culmination of a subplot that Shooter has been setting up for a couple of issues, and there’s no sci-fi explanation for Hank’s behavior. He’s just having an insecurity-fueled breakdown and taking it out on his wife.

Also, the same thing that makes Avengers v.1 #59-60 a story no one would write today — everyone behaves as if Jan’s actions are, at most, a kind of faux pas — is part of why it hasn’t adhered to Jan. More than that, it’s that Jan’s weird, disturbing behavior in the story isn’t part of a retrospectively discernible, if iadvertent pattern in her stories in the same way as Hank’s previous changes of identity and his desire to get out of superheroing, then back in again across the 1960s and 1970s.

Hank’s breakdown in the 1980s stories, by comparison, became his storyline for over a year of consecutive stories, and everyone in-universe treated it as the aftermath of domestic abuse and psychological issues. And it played well with fans partly because Hank could always be read as unstable, even from his early Ant-Man days, thanks to all the self-experimentation, identity switching, and even his falling for Jan because she looks just like a younger version of his dead wife.

Some of that is the development of a more developed (relatively speaking) focus on characters’ psychology in the 1980s as compared to the 1960s. But some of it is also the way later eras of comics took the implied elements of their own plot gimmickry a bit more seriously.

Think of all the Silver Age superhero stories in which heroes mess with their enemies’ minds…or their friends’ bodies and minds, for that matter. There’s no real way to address those stories from a “modern” perspective except by writing as if the heroes are actually horrible people. Thus the increasing tendency to play Reed Richards and Professor X as villains and stuff like *shudder* Identity Crisis.

Even there, the work is often about the story the writer wants to tell now, not the story that was told then. Hank’s fall from grace was Jim Shooter’s desire to have a story about a superhero’s flaws overwhelming them, and then it was Roger Stern’s starting point for developing the Wasp into a more significant character.

If a writer does want to have Jan fall from grace, this would be the plot to go back to. But that doesn’t seem like something that interests most writers.

Janet: “Oh good. Thanks to this handy case of mental illness, I won’t have to get myself knocked up by Hank to trick him into marrying me.”

Silver Age stories are treated differently than stories from the 1980s. There’s a lot of really stupid stuff from the Silver Age stories.

Who married those two? Is it common for someone to get married while in disguise? How would it be considered legal if he signed his signature “Yellowjacket”? Did the preacher say, “Do you Hank Pym…” only to have him respond, “I murdered him. I’m Yellowjacket.”, and the preacher responded accordingly? The preacher referred to him as “Mr. Yellowjacket”, he didn’t find that unusual, Jan told him, “Uh, yeah, that’s his real last name. Keep going.”

I have read the story, I’m just applying non-Silver Age/Roy Thomas logic to the story. I don’t know, maybe things were a lot more lax in less bureaucratic 1969, when you could just marry someone dressed as a bee and not show any identification.

I love her reaction, “Don’t try to get out of this! It’s legal! I looked it up!”.

Not to mention that maybe Janet should be excused for her very poor understanding of psychology by diagnosing Pym with “accident-induced Schizophrenia”. I mean, that’s common. Someone stubbed their toe the other day and they started hearing voices in their head, everyone was reassured when the doctor said it was just the “accident-induced Schizophrenia”. As soon as someone recovers from the injuries, that nasty case of Schizophrenia will clear right up.

Well, that handbook explanation is no less absurd than the original story. Going to the extent of marrying someone just to try cure them of schizophrenia? That’s ridiculous. Not to mention it’s the exact opposite of what you should do. Marriage isn’t a cure for insanity. It’s a leading cause.

Plus, Jan could not have a shotgun wedding to Hank, since Silver Age heroes surely didn’t have premarital sex. Well, except probably Tony Stark and, if he was a hero yet, Namor. Imperious Sex! (Thanks KG if you’re reading)

I also bet Silver Age characters could get married in costume and have it be legally binding. A question for our lawyer podcast hosts.

They probably shouldn’t try to explain Silver Age stories away using logic. Instead, they could have explained that Jan was suffering from stress-induced bipolar disorder. You know that happens a lot too.

@Moo: “Well, that handbook explanation is no less absurd than the original story. Going to the extent of marrying someone just to try cure them of schizophrenia? That’s ridiculous. Not to mention it’s the exact opposite of what you should do. Marriage isn’t a cure for insanity. It’s a leading cause.”

LOL

@Chris V: a lot of Jan’s Silver Age dialogue makes more sense if you assume she’s in a manic phase.

Also a lot of needling Hank fueling his inferiority complex. And dare I say flighty behavior.

The Hank/Jan relationship started with Jan losing her father and Hank implanting insect tissue into her body so they could fight the alien blob creature who killed Mr. Van Dyne.

Oh, and Jan is so young that she doesn’t come into her full inheritance until much later, in Avengers v.1 #43, wherein she turns 23. Since Marvel stories back then were still written as roughly proceeding in real time, and this is four years after Jan’s debut, she’s implicitly 19 when she becomes the Wasp and her relationship with Hank begins.

There’s not much from the original Ant-Man/Giant-Man/Wasp stories that looks particularly good in retrospect.

In the Silver Age writers expected readers to accept that the heroes were right just because the writers said so, no matter how little sense it made. And sometimes. it’s difficult to ignore the stories in modern times. The biggest example is Mister Miracle. Kirby’s origin of Scott was that to stop a war between Apokolips and New Genesis, Highfather agreed that his son Scott would be raised on Apokolips and Darkseid’s son Orion would be raised on New Genesis. After decades of mistreatment on Apokolips, Scott escaped. The problem is that from a modern perspective, Highfather handing his child over to a monster like Darkseid seems monstrous. To be fair to Kirby, it was strongly implied that if Highfather hadn’t made the deal, Orion would have become just as evil as Darkseid and Barda would have either turned evil or died. And Highfather seemed to know that Scott would eventually be okay through the Source. But a lot of readers still think of Highfather as a horrible parent. So in modern times, Highfather is often written as a horrible person.

One reason why many readers refuse to accept the idea of Hank being irredeemable is because Flash Thompson and Emma Frost were both abusive (to She Shan and Firestar, respectively) and readers seem to have no problem with them. In Flash’s case his hitting Sha Shan is rarely mentioned but the general idea that he inherited his father’s abusive and alcoholic traits is often mentioned. and no one has a problem with that. In Emma’s case, writers have been reluctant to term Emma’s behavior toward Firestar as abusive until recently. But in the recent West Coast Avengers series, a clear parallel was drawn between Emma and Blue Bolt- in both cases they were abused and their abusers (Emma. Blue Bolt’s father) saw the light a few years too late. Of course, as Moo pointed out, the difference is probably that neither of them STARTED out as a hero.

In any case, Gage is doing a good job in the current Battleworld series writing Hank as heroic, so we’ll see where things go from there.

@Michael: In general, I think the Silver Age definitely takes the goodness of the heroes for granted, and it makes their “goodness” the sort of thing the writers believed would appeal to boys and teenaged guys. A lot of the morality is therefore either egocentric on the part of the heroes or reflect the preferences of children.

Superman messing with Lois Lane and Jimy Olsen, as well as Lois and Lana Lang’s efforts to trap Superman into marriage all seem like writing designed to reflect boys’ ideas that girls are icky and coniving, and the ways kids often express friendship and affection for each other through mischief and superficial hostility.

Over at Silver Age Marvel, a lot of the actions of the characters are likewise built on a childlike or adolescent sense of both justice and sociality. Peter Parker is an alienated teen, so the appeal of Silver Age Spider-Man is meant to come through in seeing him lash out at his tormentors from time to time and in seeing Spider-Man be the cool, witty personality that’s a big secret to all those other people looking down on Peter.

Even stuff like the early stories in which he takes phony pictures are written as if they’re justified by J. Jonah Jameson’s exploitative treatment of Peter; he’s just getting his own back and doing what he needs to to be the breadwinner of his household. It’s not hard to see how a teenager might see all of that as “heroic” or at least justified.

Maybe the best example of all of this is the classic Imaginary Story about Superman-Red and Superman-Blue, in which everything woring out for the best takes the form of the two Superman literally brainwashing all criminals into being good and then retiring from crimefighting into marriages. It’s horrific from an adult, realist perspective, but satisfies a child’s much simpler moral fantasies of setting the world right and giving everyone a happy outcome.

The New Gods are an odd case, however, since Kirby is definitely writing from a more mythic, allegorical perspective. The trade of children as part of “The Pact” seems heavily influenced by Kirby’s interest in myth and arguably his Judaism. Highfather’s story about how a warrior named Izayah, after the Biblical prophet, communes with a higher power and turns to peace. Scott Free’s origin story resembles the “bondage to freedom” narratives of the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible.

The story of Abraham being asked to sacrifice Isaac or the cycle of the Israelites being punished by being sent into bondage to their enemies also seem horrible if we read them as a realistic relationship instead of a big allegory.

In many ways, Jim Starling was genuinely the least Kirby-like writer who could’ve taken on the New Gods, and it’s his work that really pushes the idea that Highfather is deeply flawed as a parent and as a leader.

But then, Starlin is something of an iconoclast in both the religious and colloquial senses, and his preferred heroes are always existentialist rebels against orthodoxy. His take on the New Gods is interesting on its own terms, but arguably antithetical to the classic stories.

It’s kind of a shame that Starlin’s work has been so influential in the future of that line, instead of being treated as a self-contained examination by a singular creative voice.

Or maybe the New Gods should always be written and read that way, like different refractions of a core myth, rather than as a “continuity” in which past storylines “matter” to the next interpretation of the “mythos.” (Quotation marks used here as a tribute to Kirby.)

@Michael: Kirby’s New Gods operates on a different level than your average super-hero comic, including what Omar delineates above. The exchange of children of royalty is an historic fact, not a whim of Kirby’s. His stories were often influenced by history as well as religion. Granted, readers might not have seen where Kirby was coming from in the ‘70s.

I agree with your general point, however. Kirby’s New Gods wouldn’t be an example I would use. Other Bronze Age writers, including some of my favorites (Gerber, Starlin, Englehart, Claremont) used their protagonists to express a view that they pushed as “right.” I the case of Flash Thompson and Sha Shan, I go back to the same glib argument I made regarding Hank Pym: the stories are old and (possibly, never read them) bad. Also, Flash Thompson isn’t a character with much relevance beyond the Silver Age. The only time he’s mattered in the last 40 years was his stint as Agent Venom. Almost no one cares what he did in the years between being a bully and being Venom.

I have no problem with saying that Shooter was lying. Look at his explanation: “In that story (issue 213, I think), there is a scene in which Hank is supposed to have accidentally struck Jan while throwing his hands up in despair and frustration—making a sort of “get away from me” gesture while not looking at her. Bob Hall, who had been taught by John Buscema to always go for the most extreme action, turned that into a right cross! There was no time to have it redrawn, which, to this day has caused the tragic story of Hank Pym to be known as the “wife-beater” story.” https://jimshooter.com/2011/03/hank-pym-was-not-wife-beater.html/

As the panel shows, it wasn’t a right cross, it was a left-handed slap. She’s shown knocked off her feet, which Shooter doesn’t address. Did Hall draw that on his own? In the subsequent panels, Hank doesn’t act like it was an accident but continues to verbally abuse and threaten her. When Jan is shown with a black eye, she doesn’t claim it was an accident. As for the claim that there was no time for it to be redrawn, this is Jim Shooter. As editor-in-chief, he ordered entire finished pages redone up to the deadline, the Dark Phoenix saga being a notable example. Pencils are a preliminary step in the creation process. As John Byrne has pointed out, if nothing else, the *inker* could have redrawn the panel.

Someone pointed out that Shooter tried to duck responsibility for the infamous Avengers #200 with Ms. Marvel. There’s also precedent for male on female violence. In 1976’s Superboy & The Legion of Super-Heroes 215, “The Hero Who Wouldn’t Fight”, Shooter scripted an almost identical scene with Cosmic Boy and Light Lass. https://comiczine-fa.com/fa-series-part/is-he-wearing-a-wife-beater

@neutrino- Also, in issue 212, there’s a character named Norm who hits his more powerful wife. That was obviously supposed to be foreshadowing for Hank’s situation.

Regarding Avengers 200- That’s complicated. Everyone remembers that the scene is issue 199 where Beast offers to play teddy for Carol’s baby was Michelinie’s idea and that Shooter rejected the original plot for Carol’s pregnancy which involved the Supreme Intelligence. There were four plotters listed for issue 200- Michelinie, Shooter. Perez and Bob Layton. No one remembers whose idea Marcus was. (Layton is the odd one- Perez was the artist and Shooter was the editor-in-chief but Layton usually didn’t work on Avengers.)

@Michael: “There were four plotters listed for issue 200- Michelinie, Shooter. Perez and Bob Layton. No one remembers whose idea Marcus was.”

No one wants to take credit for Marcus, at least. If I had any part in the story in Avengers 200, I’d “forget,” too.

@neutrino: I don’t like calling anyone a liar without proof, but I tend not to believe a lot of what Shooter wrote on his blog. He took credit for good things and (in the entries I read) shifted the blame for the bad stuff to others. Also, he’s written some terribly misogynistic comics (e.g. Unity) as well as that homophobic Hulk magazine story. I’m not willing to cut him much slack (post-Silver Age, at least).

What I’ve also gathered from the cluster that is Avengers #200 is that everyone was trying really hard to use as much of the art that George Perez had already drawn for the issue. I remember hearing the original plot was killed because of its similarities to a “What If?” issue, and at the time Avengers #200 came out, Denny O’Neil and Mark Grunewald were listed as the editors of that series (or at least that issue). I was always under the impression that they objected to the Avengers plot.

Though I will say, when people are recalling things from over 30 years ago, I am more likely to chalk things up to a failure of memory than accusing them of deceit.

Shooter recalling the hit as a right cross was almost certainly him misremembering. I can hardly believe that he’d intentionally make a false claim about a panel that anyone could go look at for themselves. Even if you don’t have a copy of Avengers 213, sinply Googling “Hank hits Jan” would pull up that panel. He misremembered is all.

Besides, Shooter’s bullshit was often either unverifiable or difficult to verify bullshit. Talking about disputes he had with Carol Kalish (dead) and Bill Mantlo (better off dead), for example. A lot of he said/she said type stuff. Each taken in isolation don’t mean much, but all told, Shooter racked up a lot of stories throughout his career where something went wrong or bad and the reason it went wrong or bad was because, according to him, it was entirely someone else’s fault.

Avengers #200: “Success has a thousand fathers, defeat is an orphan.” Even his harshest critics concede that Shooter introduced much needed order to the Marvel Bullpen. He mandated that the editor approve each step in the creative process. In the Dark Phoenix saga, he changed the ending. Wouldn’t he have that much control over a book he was listed as a plotter?

Not only is the panel of Hank hitting Jan readily available, Shooter included it in his blog post. Misremembering it shouldn’t be an issue. He also didn’t mention the black eye, which cemented Pym’s reputation as a wife-beater. Despite the actual image being on the post, many have accepted the explanation that the slap was never intended. Some even label the workmanlike Bob Hall as an Image-type prima donna who changed Shooter’s plot for his own ego.

This link https://comiczine-fa.com/fa-series-part/is-he-wearing-a-wife-beater points out how Cosmic Boy slapping Light Lass is “Hardly the pinnacle of partnership between the sexes that writer Jim Shooter had espoused in his earlier 1960s works.”